Abstract

We report the first genome-wide linkage analysis for reading and spelling in a sample of 403 families of twins, aged between 12 and 25 years taken from the normal population and unselected for reading ability. These traits showed heritabilities of 0.52–0.73, and support for linkage exceeded replication levels (lod>1.44) of seven of the 11 linkages reported in dyslexic samples, namely: 2q22.3, 3p12-q13, 6q11.2, 7q32, 15q21.1, 18p21, and Xq27.3. For five of these (2q22.3, 6q11.2, 7q32, 18p21, and Xq27), this study provides the first independent replication. 1p34–36 and 2p15–16 received some support, with lods of 1.2 and 0.83, respectively, whereas two regions received little support (6p23–21.3 and 11p15.5). This study also identified two novel linkages at 4p15.33-16.1 and 17p13.3, which received suggestive support (max. lod 2.08 and 1.99, respectively).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Specific reading deficits (Dyslexias) affect approximately 8% of children, despite adequate intelligence, education, and social environment.1 The disorder begins in childhood, continuing into adulthood2 and has serious social impacts.3 Since early reports of its familiality,4, 5 systematic twin studies have shown that most of this familial aggregation is due to genetic differences6 with a heritability of around 0.7.7, 8

Two forms of dyslexia have been recognized: surface dyslexia, affecting lexical processing and diagnosed by poor reading of irregular words, such as ‘YACHT’ and phonological dyslexia, diagnosed by poor phonological decoding skill, for instance reading of nonwords such as ‘SLINT’, with most cases showing affection of both types.9 Quantitative behavioural modelling suggests that normal variance in reading is heritable and that, although most genes affect both forms of reading, some genes are specific for lexical or nonlexical processing.7, 10 So whereas many of the genes accounting for this trait may be expected to exert a general effect, some should be specific for lexical processing, and some for nonlexical processing.7

Linkage and association studies of affected sib-pairs and family segregation studies have recently been reviewed in this journal11 and elsewhere.12, 13 In summary, 11 regions have been linked to reading disorder, located on chromosomes 1p34–36,14, 15, 16 2p15–16,17, 18, 19, 20 2q22.3,21 3p12-q13,22 6p23–21.3,23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30 6q11.2,31 7q32,19 11p15.5,32 15q21.1,24, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37 18p21,38, 39 and Xq27.338, 40 (see Table 1 for a cross-tabulation of linkage reports, and the diversity of phenotypes linked to each region).

Thus, whereas nearly one dozen linkages to clinical dyslexia have been reported, five have yet to be assessed in an independent sample, others have failed to replicate at least once, and none have previously been studied in a normal sample. We therefore examined which, if any, of these clinical linkages could be replicated in unselected adolescents. Second, we examined the specificity of linkages to markers of surface and phonological dyslexia: the two major subtypes of dyslexia.41 A third goal was to examine genome-wide information for possible novel linkages.

Materials and methods

Participants

Twins were initially recruited from primary schools in the greater Brisbane area, media appeals and by word of mouth, as part of ongoing studies of melanoma risk factors42, 43 and cognition,44 and form approximately one-half of the full eligible birth cohort. The sample is representative of the Queensland population for intellectual ability.45 Informed consent was obtained from all participants and parents before testing. This paper concerns data collected during 2003.

Reading and spelling phenotypes and genotyping were available for 403 twin families. This consisted of 214 pairs of DZs, 85 DZ pairs with one extra sib, 23 pairs with two extra sibs, and two with three sibs. An additional 54 MZs with one extra sib, seven with two, and one with three sibs were included in the linkage analysis using the MZ option of Merlin. MZ pairs, although not genotyped, contributed to estimation of additive genetic and shared environment effects and places an upper limit on the estimate of variance owing to a linked QTL.46 Finally, three nontwin sib pairs and 14 single co-twin-sibling pairs (11 with one sib, three with two sibs) were included. Note that although parents were not phenotyped, their genotypes (where available) still contributed to IBD estimation for siblings.

Reading and spelling assessment

Regular word, irregular word and nonword reading were assessed using the CORE,2 a reliable 120-word extended version of the Castles and Coltheart9 test with additional items added to increase the difficulty of this test for an older sample. Regular and irregular-word spelling were tested using 18 regular words and 18 irregular words from the CORE, respectively. These were presented verbally, untimed and in mixed order, the dependent variable being number of words spelled correctly to oral challenge. Nonlexical spelling was assessed by having subjects produce a regularized spelling for each of the 18 words given in the irregular spelling test. Each word was then presented verbally, and the letter string used for spelling was recorded and scored for phonological correctness from a list of acceptable regularizations. Words were repeated on request.

Each participant was contacted and interviewed over the telephone by a trained researcher in accordance with the instructions outlined above. If a blood sample for DNA analysis had not yet been obtained, this was also arranged at this time, with the subject's consent. Test scores on each of the three reading subtests and three spelling tests were calculated as a simple sum of correct items. Before analysis, all raw data were log-odds transformed to approximate normality.

Zygosity testing and genotyping

DNA extraction, zygosity determination, and genome-scan acquisition are described in detail elsewhere.47 The genome scans consisted of 796 highly polymorphic microsatellite markers (31 X-linked) at an average spacing of ∼4.8 cM with locations determined from the sex-averaged deCODE map48, 49 and interpolation of unmapped markers. Marker heterozygosity ranged between 52.6 and 91.9%. Both parental genotypes were available in 292 families, for one parent-only in 76 families, and for neither parent in 35 families. Parents were typed for between 228 and 784 markers (mean of 398±103). For twins/siblings, the number of typed markers ranged from 211 to 788, with an average of 576(±195) total markers.

Analyses

Univariate multipoint variance components (VC) linkage analysis was used at each marker to partition the phenotypic covariance matrix into genetic variance owing to the linked QTL, residual polygenic additive genetic variance, and unique environmental variance. Dominance effects (ADE model) did not appear likely as DZ correlations were not significantly lower than half the MZ correlations.50, 51, 52, 53

VC were estimated by maximum-likelihood analysis of the transformed data using the MERLIN and MINX (Merlin for the X chromosome) software packages54 with sex and age specified as (linear) covariates, and with the MZ option in MERLIN specified to allow both members of an MZ pair to be included in the analysis with their nontwin sibling/s. Linear fits for the age covariate gave equivalent fits to higher order polynomial functions within the limited range of ages in this study (12–25 years, mean 18.3±2.7). Kosambi map units (derived from the deCODE map) were transformed to Haldane units for input to Merlin. Results are reported in Haldane units. Significance of additive QTL linkage effects was assessed at each marker by comparing log10 likelihood of models including and excluding the QTL effect.55

Sex-specific difference in genetic distances arising from different female and male recombination rates can bias results in samples where parental genotypes are available only for a portion of the sample and the proportions of maternal and paternal genotypes differ significantly.56 In the present case, the percentage of cases in which only maternal or paternal genotypes were recorded was 17 and 2, respectively, meaning that the sex-averaged map will may bias LOD scores upward by around 5% in the worst case (regions with m:f distance ratios of 10).

Lander and Kruglyak's57 criterion for replication level support as lod ≥1.44 was adopted. For assessing genome-wide association, empirical P-values for significance and suggestive support for linkage were established for each phenotype using 1000 gene-dropping simulations in MERLIN, with suggestive support defined as the empirical LOD corresponding to one expected false positive per genome scan and significant linkage corresponding to one expected false positive per 20 genome scans.58 Empirical LOD scores corresponding to suggestive support were somewhat lower than the theoretical value of 2.2: being 1.66, 1.93, 1.89, 1.98, 1.86, and 1.89 for the regular, nonword, and irregular spelling measures and regular, nonword, and irregular reading measures, respectively (95% confidence interval on the empirical P-value corresponds to 0–0.003).

Results

Table 2 provides the range, mean, and standard deviation for each measure, their heritability based on a VC analysis of this sample (reported by Bates et al2), and the magnitude of significant sex and age effects. Female subjects showed increased scores for irregular word reading and both irregular- and regular-word spelling. All measures increased with age. Univariate heritabilities ranged from 0.52 for nonword spelling to 0.76 for irregular word spelling as computed in Mx.

Table 3 shows the phenotypic and genotypic intercorrelations between the six phenotypes, which are uniformly moderate to high in magnitude, and significant.

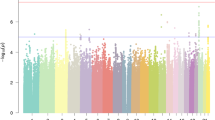

Results of the autosomal linkage scan for reading and spelling are shown in Figure 1. More detailed plots for chromosomes where support for linkage exceeded or approached replication levels as well as the novel suggestive evidence for linkage on chromosomes 4, 9 10, and 17 are shown in Figure 2. Table 4 shows the maximum LOD score and associated markers and locations for each replicated linkage. In cases where a larger linkage peak was found at a marker or region other than originally reported, both the linkage at the original region and the marker of maximum linkage (and associated trait) are shown. Also shown in Table 4 are the markers and traits associated with linkages on chromosomes 4, 9, and 17.

Autosomal linkage plots of the reading (a) and spelling (b) measures. Empirical LOD scores for suggestive support for linkage57 were 1.98, 1.86, and 1.89 for regular, nonword, and irregular reading, respectively, and, for regular, nonword, and irregular spelling were 1.66, 1.93, and 1.89, respectively.

The strongest support was found for linkages at 2q22.3, 3p12-q13 (DYX5), 6q11.2–q12 (DYX4), 7q32, 15q21 (DYX1), and 18p21 (DYX6). Strong support for linkage at 2q was found for regular-word spelling, exceeding genome-wide suggestive evidence for linkage (peak lod 2.18 at 222 cM, marker XRCC5). This peak, however, lies 70 cM distal to the original locus (marker D2S1399, 169 cM) reported by Raskind et al,21 and outside the region of overlap for the confidence intervals of the two peaks, based on a lod-drop of 1. It may still be that these peaks reflect the same gene as linkage peaks for true QTLs can vary significantly in location owing to a number of mainly stochastic factors.59

For four regions (7q32–34, 15q21, 18p21, and Xq27), linkage support fell at the same or closest marker to that reported in the original finding. Support for linkage for 7q32–q34 reached a maximum lod of 2.03 for nonword spelling at marker D7S530 (140 cM) identical to that reported in the original study.19 Irregular, regular, and nonword reading also supported linkage at the same marker with lods of 1.92, 1.13, and 1.21, respectively.

Replication-level support for linkage at 15q21 (DYX1) affecting regular word spelling (lod 1.89) fell at D15S994, our closest marker to the D15S132 satellite, which defined the peak identified by Schulte-Körne et al,34 but which was not included in our marker panel. This marker also defined the peak in the UK study. Similarly, the replication peak for linkage at 18p21 (the putative DYX6 locus) coincided with the strongest marker from the UK sample reported by Fisher et al38 (marker D18S464, 34.50 cM, lod=1.70), and our strongest signal (marker D18S478, 54.878 cM, lod=2.00) coinciding with the strongest marker from the US sample. Finally, linkage at Xq27 was supported, with linkage peaking at the same markers (DXS1227 through DXS8091) implicated in the original report of de Kovel et al,40 with a peak lod of 1.09 at DXS9908 in the present sample.

For DYX5 (3p12-q13) support exceeded replication levels (max. lod 1.66 at marker D3S1292 for irregular reading), within 20 cM of the peak reported by Nopola-Hemmi et al.22 Further support for this being the same locus as identified by Nopola-Hemmi et al was provided by the overlap of the drop-lod 1 region of this linkage and the original peak, with lods of 1.04 at marker D3S1289 for nonword reading (our closest marker to D3S3665 which defined the peak in the original report) and a lod of 1.19 for nonword spelling at marker D3S4542, some 20 cM proximal to the original locus,22 evidence for a gene or genes in the locus identified by Nopola-Hemmi.

Although peaking at the same marker previously reported by Grigorenko et al,15 support for linkage for DYX8 (chromosome 1: marker D1S234) fell short of the replication level with a peak lod of 1.2 for nonword reading. Support for linkage was low and flat across 6p, with no support for any effect at 6p23–21.3 (DYX2) for any phenotype for reading or spelling (peak LOD score 0.16). Support for linkage at 11p15.5 (putative DYX7) was also weak (max. lod 0.62 for irregular reading at marker D11S1338), with no peaks elsewhere on the chromosome. Similarly for the putative DYX3, two distinct peaks were present within 18 cM distal of the D2S337-D2S286 linkage identified by Francks et al20 at 2p15–16, with a lod of 0.83 at marker D2S1360 for nonword spelling; and a second peak of 1.04 at marker D2S2972 for regular word reading.

Linkage for DYX4 (6q11.2–q12), support at the original locus of maximum evidence for linkage exceeded replication levels (linkage for irregular word spelling, max. lod of 1.59 at D6S462), but a considerably stronger peak lay distal to this at D6S262 (lod=2.04, 130.7 cM), again for irregular word spelling. It is noteworthy that the small set of markers examined by Petryshen et al31 did not extend beyond 6q12, as they designed the marker set primarily to explore the 6p region, leaving open the possibility that the true region of maximum linkage in their sample was more distal than reported, and that the present peak at D6S262 refines the locus as more distal than originally reported.

Two new regions exceeded the empirical criteria for suggestive evidence for linkage. The strongest of these novel linkages was found for irregular-word reading on chromosome 4 (marker AD4S403; 29.21 cM, lod=2.08; empirical threshold for suggestive support for linkage= 1.89). The irregular-word spelling counterpart also supported linkage, albeit weaker, peaking at a lod of 1.43 at marker D4S2633. Irregular-word spelling showed suggestive support at chromosome 17, peaking at marker D17S831 (5.89 cM) with a lod of 1.99 (exceeding the empirical threshold for suggestive evidence of linkage =1.89).

Discussion

Most previous studies of dyslexia have used patient samples. In contrast, we have administered reading and spelling tests by telephone to a sample of twins and their siblings without selection for any cognitive or other trait, that is, a sample of normally varying adolescents.

The present study of an normal sample supported nine of the 11 regions previously identified only in samples selected for dyslexia, with seven of these loci supported at the level of independent replication. In addition to replicating most prior reports of linkage from clinical samples, two new regions exceeded the empirical criteria for suggestive support. The strongest of these novel effects was found for irregular-word reading on chromosome 4p15 and for irregular-word spelling on chromosome 17p13.

For five of the seven replicated linkages (2q,21 6q11.2–q12,31 7q32,19 18p21,38 and Xq2740), the present paper forms the first replication in a sample outside those reported in the original papers. Replication maxima also fell close to the loci reported in original reports. For loci 18p21, 7q32, and Xq27, markers identical to those used in the original reports defined the maxima. In the case of 15q21, the linkage peak was to the marker in our microsatellite array closest to that in the original report.34 Our results, then, suggest that loci identified in dyslexic groups play a role in normal reading and spelling although further examination is needed.

Two linkage regions received little support in the present study: 6p21–23 and 11p. Given our sample size, failure to find evidence for linkage cannot be taken as strong evidence against the linkage. It may also be the case that the genes in these regions are selective for severe forms of reading problem not present in our general sample. In the case of 6p21–23, the failure to find linkage is compatible with several previous nonreplications at this locus.33, 34, 60 Chapman et al33 noted that in most cases of nonreplication, the tests of reading used were unspeeded, whereas successful replications such as that of Kaplan et al29 used timed measures of reading aloud. It is possible, then, that 6p is related to processes determining the speed, rather than accuracy of reading, or at least that the 6p linkage region is highlighted during speeded reading. Also, two candidate genes have now been reported for 6p23–21.3: KIAA031961, 62 and DCDC2.63 Because of the greater power of association studies, we are examining these genes in our sample at present.64 By contrast with 6p, the 11p15.5 region has a weaker background of previous support.32 The lack of evidence for linkage in this region might suggest that this linkage is related to ADHD and only appears in dyslexia samples owing to comorbidity of ADHD with dyslexia,65 in which case DYX7 would not, in fact, be related to reading-specific functions.

The present data shed some light on observed behavioural correlates of reading such as sex differences, on theoretical proposals for mechanisms underlying reading such as speed of lexical access as a determinant of reading skill,66 and on the range of languages and geographical regions in which chromosomal regions identified to date play a role in the development of reading. Support for linkage on the X chromosome and previous reports38, 40 suggest a mechanism for observed sex differences in dyslexia. The role of sex in determining reading disorder is an important and open topic, especially given recent reports that males are more at risk67 and that severe risk is more highly heritable in males at least before age 8 years.68 More research is needed in this area, given the contradictory state of reports from older samples,2, 69 but clinical risk rates are indisputably elevated for younger males.

The replication support for linkage at 2q22.3 focuses attention on the ability of genetic studies to dissect component tasks within reading. Raskind et al21 reported that linkage support at 2q was specific for speed of nonword reading (‘phonological decoding’), and was unrelated to accuracy on this task. This is the first report of such a within-task specificity, and as such was of interest in potentially dissecting the reading phenotype. Although our study did not contain pure speeded measures, instead focusing on accuracy, modest support for linkage was found proximal to the original locus for regular word reading accuracy with stronger evidence (lod 2.18 at marker XRCC5) distal to 2q22.3, again for a regular-word phenotype (spelling). Wolf's double-deficit hypothesis of reading suggests that lexical access speed is a basis for lexical skill66, 70 and would predict that a ‘speed’ endophenotype such as reported by Raskind et al21 should associate with regular word reading accuracy as found here. Clearly, more studies are needed, both to narrow the region of interest and to better understand the phenotype, and how speeded reading might be related to our spelling task.

Several of the loci including 2p and 7q have now been examined in a diverse range of language families and geographical regions. For instance, chromosome 2p has been linked to reading across a range of geographical boundaries and language families including Norwegian,17 Canadian,18 Finnish,19 and English20, 38 samples. Likewise, the replication of linkage support at 7q32 in an English-speaking unselected Australian sample suggests that it is not specific to the original sample, or language (the original report being Finnish19). This suggests that several of the genes identified may affect reading in ways common to most or all languages and, that at least some linkages may operate across broad geographical regions.

The status of candidate genes has recently been reviewed,13 with support for candidates at DYX1 (DYX1C171), DYX2 (KIAA031961, 62 and DCDC263), and DYX5 (ROBO172) being involved in at least some cases of dyslexia. For most regions, then, candidate genes are unknown, but the finding that each of the above four genes play putative roles in neuronal migration during the laying down of the nervous system may guide the search for candidates at the other loci reported here and elsewhere.

In summary, our data provide the first reported replication of five linkages: 2q22.3, 6q11.2, 7q32, 18p21, and Xq27. Additional support was found for the four well established loci: 3p12-q13 (DYX5), 15q21.1 (DYX1), 1p34–36 (DYX8), and 2p15–16 (DYX3), with a clear failure to find support only in two cases (6p23–21.3 (DYX2) and 11p15.5 (DYX7)). This level of support for linkage in a normal, unselected sample, for linkages previously reported in dyslexic patient samples, as well as novel linkages is encouraging, and developments in positional candidates provide optimism that further studies can identify genes, and contribute to a mechanism for the biological basis of both reading disorder, and normal variation in reading.

References

Shaywitz SE, Shaywitz BA, Fletcher JM, Escobar MD : Prevalence of reading disability in boys and girls. Results of the Connecticut Longitudinal Study. JAMA 1990; 264: 998–1002.

Bates TC, Castles A, Coltheart M, Gillespie N, Wright M, Martin NG : Behaviour genetic analyses of reading and spelling: a component processes approach. Aust J Psychol 2004; 56: 115–126.

Maughan B, Pickles A, Hagell A, Rutter M, Yule W : Reading problems and antisocial behaviour: developmental trends in comorbidity. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1996; 37: 405–418.

Hallgren B : Specific dyslexia: a clinical and genetic study. Acta Psychiatrica et Neurologica Scandinavica 1950; 65 (Suppl): 1–287.

Thomas CJ : Congenital ‘word-blindness’ and its treatment. Ophthalmoscope 1905; 3: 380–385.

DeFries JC, Fulker DW, LaBuda MC : Evidence for a genetic aetiology in reading disability of twins. Nature 1987; 329: 537–539.

Bates T, Castles A, Luciano M, Wright M, Coltheart M, Martin N : Genetic and environmental bases of reading and spelling: a unified genetic dual route model. Read Writ 2007; 10: 1–25.

Gayan J, Olson RK : Genetic and environmental influences on individual differences in printed word recognition. J Exp Child Psychol 2003; 84: 97–123.

Castles A, Coltheart M : Varieties of developmental dyslexia. Cognition 1993; 47: 149–180.

Bates TC, Castles A, Coltheart M et al: Genetics of reading and spelling: shared genes across modalities, but different genes for lexical and nonlexical processing. Meeting of the Society for the Scientific Study of Reading. Amsterdam: The Netherlands, 2004.

Williams J, O'Donovan MC : The genetics of developmental dyslexia. Eur J Hum Genet 2006; 14: 681–689.

Bates TC : Genes for reading and writing. London Rev Educ 2006; 4: 31–47.

Fisher SE, Francks C : Genes, cognition and dyslexia: learning to read the genome. Trends Cogn Sci 2006; 10: 250–257.

Rabin M, Wen XL, Hepburn M, Lubs HA, Feldman E, Duara R : Suggestive linkage of developmental dyslexia to chromosome 1p34–p36. Lancet 1993; 342: 178.

Grigorenko EL, Wood FB, Meyer MS, Pauls JE, Hart LA, Pauls DL : Linkage studies suggest a possible locus for developmental dyslexia on chromosome 1p. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2001; 105: 120–129.

Tzenova J, Kaplan BJ, Petryshen TL, Field LL : Confirmation of a dyslexia susceptibility locus on chromosome 1p34–p36 in a set of 100 Canadian families. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2004; 127: 117–124.

Fagerheim T : A new gene (DYX3) for dyslexia is located on chromosome 2. J Med Genet 1999; 36: 664–669.

Petryshen TL, Kaplan BJ, Hughes ML, Tzenova J, Field LL : Supportive evidence for the DYX3 dyslexia susceptibility gene in Canadian families. J Med Genet 2002; 39: 125–126.

Kaminen N, Hannula-Jouppi K, Kestila M et al: A genome scan for developmental dyslexia confirms linkage to chromosome 2p11 and suggests a new locus on 7q32. J Med Genet 2003; 40: 340–345.

Francks C, Fisher SE, Olson RK et al: Fine mapping of the chromosome 2p12–16 dyslexia susceptibility locus: quantitative association analysis and positional candidate genes SEMA4F and OTX1. Psychiatr Genet 2002; 12: 35–41.

Raskind WH, Igo RP, Chapman NH et al: A genome scan in multigenerational families with dyslexia: identification of a novel locus on chromosome 2q that contributes to phonological decoding efficiency. Mol Psychiatry 2005; 10: 699–711.

Nopola-Hemmi J, Myllyluoma B, Haltia T et al: A dominant gene for developmental dyslexia on chromosome 3. J Med Genet 2001; 38: 658–664.

Cardon LR, Smith SD, Fulker DW, Kimberling WJ, Pennington BF, DeFries JC : Quantitative trait locus for reading disability on chromosome 6. Science 1994; 266: 276–279.

Grigorenko EL, Wood FB, Meyer MS et al: Susceptibility loci for distinct components of developmental dyslexia on chromosomes 6 and 15. Am J Hum Genet 1997; 60: 27–39.

Cardon LR, Smith SD, Fulker DW, Kimberling WJ, Pennington BF, DeFries JC : Quantitative trait locus for reading disability: correction. Science 1995; 268: 1553.

Grigorenko EL, Wood FB, Golovyan L, Meyer M, Romano C, Pauls D : Continuing the search for dyslexia genes on 6p. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2003; 118: 89–98.

Fisher SE, Marlow AJ, Lamb J et al: A quantitative-trait locus on chromosome 6p influences different aspects of developmental dyslexia. Am J Hum Genet 1999; 64: 146–156.

Turic D, Robinson L, Duke M et al: Linkage disequilibrium mapping provides further evidence of a gene for reading disability on chromosome 6p21.3–22. Mol Psychiatry 2003; 8: 176–185.

Kaplan DE, Gayan J, Ahn J et al: Evidence for linkage and association with reading disability on 6p21.3–22. Am J Hum Genet 2002; 70: 1287–1298.

Gayan J, Smith SD, Cherny SS et al: Quantitative-trait locus for specific language and reading deficits on chromosome 6p. Am J Hum Genet 1999; 64: 157–164.

Petryshen TL, Kaplan BJ, Fu Liu M et al: Evidence for a susceptibility locus on chromosome 6q influencing phonological coding dyslexia. Am J Med Genet 2001; 105: 507–517.

Hsiung GY, Kaplan BJ, Petryshen TL, Lu S, Field LL : A dyslexia susceptibility locus (DYX7) linked to dopamine D4 receptor (DRD4) region on chromosome 11p15.5. Am J Med Genet B: Neuropsychiat Genet 2004; 125: 112–119.

Chapman NH, Igo RP, Thomson JB et al: Linkage analyses of four regions previously implicated in dyslexia: confirmation of a locus on chromosome 15q. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2004; 131: 67–75.

Schulte-Körne G, Grimm T, Nothen MM et al: Evidence for linkage of spelling disability to chromosome 15. Am J Hum Genet 1998; 63: 279–282.

Nothen MM, Schulte-Korne G, Grimm T et al: Genetic linkage analysis with dyslexia: evidence for linkage of spelling disability to chromosome 15. Eur Child Adolescent Psychiatry 1999; 8 (Suppl 3): 56–59.

Nopola-Hemmi J, Taipale M, Haltia T, Lehesjoki AE, Voutilainen A, Kere J : Two translocations of chromosome 15q associated with dyslexia. J Med Genet 2000; 37: 771–775.

Morris DW, Robinson L, Turic D et al: Family-based association mapping provides evidence for a gene for reading disability on chromosome 15q. Hum Mol Genet 2000; 9: 843–848.

Fisher SE, Francks C, Marlow AJ et al: Independent genome-wide scans identify a chromosome 18 quantitative-trait locus influencing dyslexia. Nat Genet 2001; 30: 86–91.

Marlow AJ, Fisher SE, Francks C et al: Use of multivariate linkage analysis for dissection of a complex cognitive trait. Am J Hum Genet 2003; 72: 561–570.

de Kovel CGF, Hol FA, Heister JGAM et al: Genomewide scan identifies susceptibility locus for dyslexia on Xq27 in an extended Dutch family. J Med Genet 2004; 41: 652–657.

Castles A, Bates TC, Coltheart M : John Marshall and the developmental dyslexias. Aphasiology 2006; 20: 871–892.

McGregor B, Pfitzner J, Zhu G et al: Genetic and environmental contributions to size, color, shape, and other characteristics of melanocytic naevi in a sample of adolescent twins. Genet Epidemiol 1999; 16: 40–53.

Zhu G, Duffy DL, Eldridge A et al: A major quantitative-trait locus for mole density is linked to the familial melanoma gene CDKN2A: a maximum-likelihood combined linkage and association analysis in twins and their sibs. Am J Hum Genet 1999; 65: 483–492.

Wright MJ, Martin NG : The Brisbane Adolescent Twin Study: outline of study methods and research projects. Aust J Psychol 2004; 56: 65–78.

Luciano M, Wright MJ, Geffen GM, Geffen LB, Smith GA, Martin NG : A genetic investigation of the covariation among inspection time, choice reaction time, and IQ subtest scores. Behav Genet 2004; 34: 41–50.

Evans DM, Medland SE : A note on including phenotypic information from monozygotic twins in variance components QTL linkage analysis. Ann Hum Genet 2003; 67: 613–617.

Zhu G, Evans DM, Duffy DL et al: A genome scan for eye color in 502 twin families: most variation is due to a QTL on chromosome 15q. Twin Res 2004; 7: 197–210.

Leal SM : Genetic maps of microsatellite and single-nucleotide polymorphism markers: are the distances accurate? Genet Epidemiol 2003; 24: 243–252.

Kong A, Gudbjartsson DF, Sainz J et al: A high-resolution recombination map of the human genome. Nat Genet 2002; 31: 241–247.

Amos CI : Robust variance-components approach for assessing genetic linkage in pedigrees. Am J Hum Genet 1994; 54: 535–543.

Eaves LJ, Neale MC, Maes H : Multivariate multipoint linkage analysis of quantitative trait loci. Behav Genet 1996; 26: 519–525.

Fulker DW, Cherny SS : An improved multipoint sib-pair analysis of quantitative traits. Behav Genet 1996; 26: 527–532.

Almasy L, Blangero J : Multipoint quantitative-trait linkage analysis in general pedigrees. Am J Hum Genet 1998; 62: 1198–1211.

Abecasis GR, Cherny SS, Cookson WO, Cardon LR : Merlin – rapid analysis of dense genetic maps using sparse gene flow trees. Nat Genet 2002; 30: 97–101.

Williams JT, Blangero J : Comparison of variance components and sibpair-based approaches to quantitative trait linkage analysis in unselected samples. Genet Epidemiol 1999; 16: 113–134.

Fingerlin TE, Abecasis GR, Boehnke M : Using sex-averaged genetic maps in multipoint linkage analysis when identity-by-descent status is incompletely known. Genet Epidemiol 2006; 30: 384–396.

Lander E, Kruglyak L : Genetic dissection of complex traits: guidelines for interpreting and reporting linkage results. Nat Genet 1995; 11: 241–247.

Churchill GA, Doerge RW : Empirical threshold values for quantitative trait mapping. Genetics 1994; 138: 963–971.

Roberts SB, MacLean CJ, Neale MC, Eaves LJ, Kendler KS : Replication of linkage studies of complex traits: an examination of variation in location estimates. Am J Hum Genet 1999; 65: 876–884.

Petryshen TL, Kaplan BJ, Liu MF, Field LL : Absence of significant linkage between phonological coding dyslexia and chromosome 6p23–21.3, as determined by use of quantitative-trait methods: confirmation of qualitative analyses. Am J Hum Genet 2000; 66: 708–714.

Cope NA, Harold D, Hill G et al: Strong evidence that KIAA0319 on chromosome 6p is a susceptibility gene for developmental dyslexia. Am J Hum Genet 2005; 76: 581–591.

Francks C, Paracchini S, Smith SD et al: A 77-kilobase region of chromosome 6p22.2 is associated with dyslexia in families from the United Kingdom and from the United States. Am J Hum Genet 2004; 75: 1046–1058.

Meng H, Smith SD, Hager K et al: From the cover: DCDC2 is associated with reading disability and modulates neuronal development in the brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005; 102: 17053–17058.

Luciano M, Lind P, Wright MJ, Martin NG, Bates TC : Association of KIAA0319 to reading in an unselected sample. Biological Psychiatry 2006; in press.

Willcutt EG, Pennington BF : Comorbidity of reading disability and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: differences by gender and subtype. J Learn Disabil 2000; 33: 179–191.

Wolf M, Bowers PG, Biddle K : Naming-speed processes, timing, and reading: a conceptual review. J Learn Disabil 2000; 33: 387–407.

Rutter M, Caspi A, Fergusson D et al: Sex differences in developmental reading disability: new findings from 4 epidemiological studies. JAMA 2004; 291: 2007–2012.

Harlaar N, Spinath FM, Dale PS, Plomin R : Genetic influences on early word recognition abilities and disabilities: a study of 7-year-old twins. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2005; 46: 373–384.

Wadsworth S, DeFries JC : Genetic etiology of reading difficulties in boys and girls. Twin Res 2005; 8: 594–601.

Castles A, Coltheart M : Does phonological awareness help children learn to read? Cognition 2004; 91: 77–111.

Taipale M, Kaminen N, Nopola-Hemmi J et al: A candidate gene for developmental dyslexia encodes a nuclear tetratricopeptide repeat domain protein dynamically regulated in brain. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 2003; 100: 11553–11558.

Hannula-Jouppi K, Kaminen-Ahola N, Taipale M et al: The axon guidance receptor gene ROBO1 is a candidate gene for developmental dyslexia. PLoS Genet 2005; 1: e50.

Smith SD, Kimberling WJ, Pennington BF : Screening for multiples genes influencing dyslexia. Read Writ Interdiscipl J 1991; 3: 285–298.

Smith SD, Kimberling WJ, Pennington BF, Lubs HA : Specific reading disability: identification of an inherited form through linkage analysis. Science 1983; 219: 1345–1347.

Field LL, Kaplan BJ : Absence of linkage of phonological coding dyslexia to chromosome 6p23–p21.3 in a large family data set. Am J Hum Genet 1998; 63: 1448–1456.

Marino C, Giorda R, Vanzin L et al: A locus on 15q15-15qter influences dyslexia: further support from a transmission/disequilibrium study in an Italian speaking population. J Med Genet 2004; 41: 42–46.

Stein CM, Schick JH, Gerry Taylor H et al: Pleiotropic effects of a chromosome 3 locus on speech–sound disorder and reading. Am J Hum Genet 2004; 74: 283–297.

Schumacher J, Konig IR, Plume E et al: Linkage analyses of chromosomal region 18p11-q12 in dyslexia. J Neural Transm 2006; 113: 417–423.

Acknowledgements

We thank the twins and their parents for their cooperation, Anjali Henders for blood processing, and Megan Campbell for DNA extraction. Phenotype collection was funded by ARC Grants (A79600334, A79906588, A79801419, DP0212016, DP0343921) and genotyping at the Australian Genome Research Facility supported by the Australian NHMRC's Program in Medical Genomics (NHMRC-219178) and the Center for Inherited Disease Research (CIDR; Director, Dr Jerry Roberts) at The Johns Hopkins University. CIDR is fully funded through a federal contract from the National Institutes of Health to The Johns Hopkins University (contract number N01-HG-65403). Dr Luciano is supported by an Australian Research Council Postdoctoral Fellowship (DP0449598).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bates, T., Luciano, M., Castles, A. et al. Replication of reported linkages for dyslexia and spelling and suggestive evidence for novel regions on chromosomes 4 and 17. Eur J Hum Genet 15, 194–203 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201739

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201739

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Hypothesis-driven genome-wide association studies provide novel insights into genetics of reading disabilities

Translational Psychiatry (2022)

-

A theoretical molecular network for dyslexia: integrating available genetic findings

Molecular Psychiatry (2011)

-

Familial Dyslexia in a Large Swedish Family: A Whole Genome Linkage Scan

Behavior Genetics (2011)

-

Genome Scan for Spelling Deficits: Effects of Verbal IQ on Models of Transmission and Trait Gene Localization

Behavior Genetics (2011)

-

In Search of the Perfect Phenotype: An Analysis of Linkage and Association Studies of Reading and Reading-Related Processes

Behavior Genetics (2011)