Abstract

The lack of cochlear regenerative potential is the main cause for the permanence of hearing loss. Albeit quiescent in vivo, dissociated non-sensory cells from the neonatal cochlea proliferate and show ability to generate hair cell-like cells in vitro. Only a few non-sensory cell-derived colonies, however, give rise to hair cell-like cells, suggesting that sensory progenitor cells are a subpopulation of proliferating non-sensory cells. Here we purify from the neonatal mouse cochlea four different non-sensory cell populations by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). All four populations displayed proliferative potential, but only lesser epithelial ridge and supporting cells robustly gave rise to hair cell marker-positive cells. These results suggest that cochlear supporting cells and cells of the lesser epithelial ridge show robust potential to de-differentiate into prosensory cells that proliferate and undergo differentiation in similar fashion to native prosensory cells of the developing inner ear.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The mammalian cochlea is a beautiful and complex organ containing sensory hair cells and a great variety of non-sensory cells. Sensory hair cells are vulnerable to ototoxic insults such as traumatic noise, certain drugs and the effects of aging1. This vulnerability combined with lack of hair cell regeneration is the leading cause of incurable hearing loss affecting hundreds of millions of patients worldwide. Cochlear non-sensory cells are highly specialized, for example to provide mechanical support or essential physiological accessory functions such as regulation of ion homeostasis. In non-mammalian vertebrates, such as birds, the non-sensory supporting cells that are closely associated with hair cells serve as somatic stem cells with ability to regenerate lost hair cells and hearing2. Mammalian supporting cells, however, are mitotically quiescent and do not replace lost hair cells. Nevertheless, several reports have shown that cochlear non-sensory cells including supporting cells are able to proliferate and to serve as progenitor cells with the ability to grow into epithelial patches containing hair cell- and supporting cell-like cells3,4,5,6,7,8,9. This regenerative potential is rare. Typically less than 1% of the dissociated cells are able to grow into colonies and only a small fraction of these colonies ultimately give rise to hair cell marker-expressing cells6,7. Furthermore, the proliferative ability of dissociated cochlear cells is transient and it ceases after the second postnatal week in mice7,9.

Here we investigated the proliferative capacity as well as the potential to re-differentiate into sensory epithelia of different cell populations isolated from the neonatal cochlea. We used fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to purify 4 non-sensory cell populations as well as sensory hair cells. All four non-sensory cell populations showed strong proliferative potential. Notably, the cells representing the lesser epithelial ridge (LER, or outer sulcus) including the organ of Corti supporting cells were not only proliferative but also robustly gave rise to epithelial cell patches harboring hair cell- and supporting cell-like cells. These results suggest that the cells that are closely associated with the sensory hair cells appear to have the strongest intrinsic regenerative capacity, whereas other cochlear non-sensory cells are proliferative, but less capable of serving as hair cell and supporting cell-progenitors.

Results

Purification of different neonatal organ of Corti cell types

To mark different types of supporting cells, we utilized the surface markers CD271, CD326 and CD146, which are differentially expressed in the postnatal day (P) 3 cochlea (Fig. 1a). CD271 (p75 neurotrophin receptor) labels pillar and Hensen's cells9, CD326 (epithelial cell adhesion molecule, EpCAM) was detectable in all supporting cells and sensory hair cells and has previously been shown to be highly expressed in the newborn mouse inner ear10 and CD146 (melanoma cell adhesion molecule, MCAM), which labeled the cells of the greater epithelial ridge and afferent neurite-associated cells below the organ of Corti basilar membrane. Because the expression pattern of all three CD markers was dynamic during neonatal maturation of the organ of Corti, we focused our analyses on organ of Corti preparations from P3, which is within the neonatal two-week period wherein some cochlear cells display in vitro-capacity for de-differentiation, proliferation and multipotency to differentiate into supporting cell- and hair cell-like cells7,9.

Dissection of the neonatal organ of Corti into 5 distinct cell populations.

a, Immunohistological staining with CD271, CD326 and CD146 of middle-turn cryosections of fixed P3 Math1-nGFP cochlea. Primary antibodies were visualized with Cy5-conjugated secondary antibodies (shown in red), the hair cells are nGFP-positive (shown in green). b, Fragment of a typical P3 Math1-nGFP cochlear duct used for cell dissociation and FACS analysis. The lesser (LER) and greater epithelial ridges (GER) are indicated; hair cells are nGFP-positive. c, FACS regimen. 2.3 ±0.2% of the total viable cells were GFP+ (green box). c', 2.6 ±0.3% of the GFP− cells were CD271High (red box) and c”, 7.2 ±0.7% of the GFP−/CD271Low cells were CD326+/CD146Low (light blue box), 21.2 ±2.0% were CD326+/CD146High (dark blue box) and 63.2 ±2.9% were CD326− (yellow box) (n = 9). d, Shown is a heat map representing similarity and divergence in the gene expression levels of the 1,000 most divergent genes among 13 array data sets obtained with independent sorted cochlear cell populations.

P3 Math1-nGFP mouse cochlear sensory epithelia6, consisting of greater and lesser epithelial ridges (GER & LER) including the organ of Corti with nGFP-positive hair cells, were dissected (Fig. 1b), dissociated into single cells and labeled with propidium iodide and the three CD marker antibodies. The cell suspension was subjected to FACS purification. 83.6 ±2.8% of the total input of cells were viable, determined by exclusion of propidium iodide. Only viable cells were collected into 5 distinct populations: GFP+ cells (Fig. 1c), GFP−/CD271High (Fig. 1c'), as well as GFP−/CD271Low/CD326+/CD146Low, GFP−/CD271Low/CD326+/CD146High and GFP−/CD271Low/CD326− (Fig. 1c”). The sorted populations were re-analyzed via flow cytometry, revealing >95% purity. The different populations were subjected to gene array-based mRNA expression analysis, which confirmed a high degree of homogeneity among the three independent biological samples for each group (Fig. 1d). The gene array data analysis also revealed that each population was distinctly different from the others, showing enrichment of sensory hair cell markers in GFP+ cells, monocyte/macrophage markers in GFP−/CD271High cells11,12, as well as LER and supporting cell markers such as BMP4, Prox1, p75 and FGFR313,14,15,16 in GFP−/CD271Low/CD326+/CD146Low cells (Fig. 2). GFP−/CD271Low/CD326+/CD146High cells expressed genes that are either specific for the GER such as Crabp1/217, or strongly enriched in the GER region such as Foxg118, or expressed in homologous regions such as Cdh4, which is found in homogene cells in the avian basilar papilla19. In contrast, the GFP−/CD271Low/CD326− cell population consisted of cells expressing sub-basilar membrane cell markers including Mpz, Mial and Aqp120,21,22,23. Based on this analysis, we hypothesize that flow cytometric cell separation reliably enriched for organ of Corti sensory hair cells, monocytes/macrophages, LER and supporting cells, GER cells, as well as sub-basilar membrane cells (Fig. 3).

Selected genes and their maximum differential expression within the 5 groups of FACS-sorted cells.

Markers known to be specific for hair cells are indicated with light green, markers known to be specific for other cell types or cochlear regions are indicated as follows: monocytes/macrophages in light red, sub-basilar membrane in light yellow, LER and supporting cells in light blue and GER in purple. In all cases, the maximum expression indicated by x-fold enrichment over the average of all other populations matched the distinct population, which is indicated with saturated colors.

Schematic drawing to visualize the cellular identity of the five FACS-sorted cell populations.

Based on gene array analysis and comparison of marker gene expression levels, we propose a model in which the GFP+ cells (shown in green) represent the inner and outer hair cells (IHC, OHC), GFP−/CD271High (shown in red) represent monocytes/macrophages, GFP−/CD271Low/CD326+/CD146Low (light blue) represent LER and organ of Corti supporting cells, GFP−/CD271Low/CD326+/CD146High (dark blue) represent GER cells and GFP−/CD271Low/CD326− (yellow) represent cells located below the basilar membrane.

Dissociated cells above the basilar membrane display greater proliferative potential than sub-basilar membrane cells

We tested the proliferative potential of the different cochlear cell subtypes in clonal floating colony (sphere) formation assays, in which the cells are cultured non-adherently at low density7,24. After 5 days in culture, the GFP−/CD271High and GFP−/CD271Low/CD326+/CD146High cells gave rise to 5.1±0.8 and 5.1±1.4 spheres, respectively, per 300 cells plated (Fig 4a), which is a 2–4-fold enrichment of sphere formation capacity when compared with our previous reports using cochlear sensory epithelium cells in identical conditions without enrichment of supporting cell subtypes6,7,8. 1.5 ±0.6 of 300 GFP−/CD271Low/CD326+/CD146Low cells (n = 6) grew into spheres, whereas only 0.07 ±0.4 spheres per 300 GFP−/CD271Low/CD326− cells formed spheres. All spheres, except for irregular shaped ones that formed from GFP−/CD271Low/CD326− cells, were initially solid and transitioned into hollow spheres when cultured for longer periods, similar to previous reports of cochlear sphere shapes6. When we included 5-ethyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) in the culture media during the first 36h of the sphere formation period, we found that approximately 90% of the sphere cells had incorporated the thymidine analogue during S-phase, which shows that the spheres formed by mitotic cell proliferation (Fig. 4b). At low plating concentrations of 3 cells/µl that are regarded as clonal analysis7,8,25, we assume that the majority of spheres that formed were clonal.

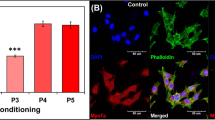

Colony formation capacity of cochlear non-sensory cell populations.

a, Sorted cells were cultured with a density of 3 cells/µl in non-adherent conditions and spheres were counted after 5 days (n = 6). * indicates p<0.05. b, EdU incorporation into spheres after 5 days in culture (n = 3–4). c, 3-day-old colonies on mitotically inactivated chicken utricle stroma-derived feeder cells, immunolabeled with antibodies to E-cadherin (green), visualized EdU incorporation (red) and nuclear DNA staining with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, blue). d, Number of colonies grown from 5,000 individual cells of each of the different non-sensory populations after 1, 3, 7 and 14 days of culture (n = 3–12). e, Colony cell numbers at the time points indicated. Color codes are indicated in Figs. 1 and 3.

Sphere formation assays have been mainly used for isolation of progenitor and stem cells from neural tissue24,26,27, but the growth potential of epithelial cells might not be adequately revealed with non-adherent assays. Consequently, we employed an attached cell colony formation assay as alternative method to evaluate the proliferative and differentiation potential FACS-isolated cochlear cell populations. The cells were cultured for 3–5 days on mitotically inactivated feeder cells derived from a primary culture of chicken utricle stromal cells and the number of colonies identified with antibodies to E-cadherin was counted and assessed for EdU incorporation. GFP−/CD271Low/CD326− cells had low capacity for colony formation, whereas cells from the three other populations robustly grew into colonies of 10–50 cells (Fig. 4c–e). GFP−/CD271Low/CD326+/CD146Low cells, which were less potent to give rise to spheres (Fig. 4a), were as potent as the GFP−/CD271High and GFP−/CD271Low/CD326+/CD146High cells in the attached cell colony formation assay. EdU incorporation into colonies that formed in this assay was >90% when assessed after 3–5 days in culture (Fig. 4c), showing that the colonies arose through mitotic cell proliferation. Colony numbers increased from the third day in culture until day 14 (Fig. 4d), an indication that some colony-forming cells needed time before proliferating. The colony cell numbers of GFP−/CD271High, GFP−/CD271Low/CD326+/CD146Low and GFP−/CD271Low/CD326− colonies after 14 days in culture was between 20 and 75 cells. In contrast, GFP−/CD271Low/CD326+/CD146High colonies grew significantly larger and generally consisted of at least double as many cells as the colonies that grew from the other cell populations (Fig. 4e). We observed a poor survival of the chicken feeder cells when cocultured with GFP−/CD271High cells, which is probably due to the macrophages that were a major fraction of this cell population.

GFP−/CD271Low/CD326+/CD146Low cells robustly generate hair cell-like cells

Sensory hair cells of Math1-nGFP mice express the GFP-reporter at an early stage of development, very likely soon after they acquire hair cell identity7,28. To identify and to monitor the occurrence of nascent hair cell-like cells, we quantified the number of nGFP-positive cells during the initial colony-formation period until 14 days in vitro (Fig. 5a). Colonies from GFP−/CD271Low/CD326−, GFP−/CD271High and GFP−/CD271Low/CD326+/CD146High cells exhibited few cells with nGFP expression. In GFP−/CD271Low/CD326+/CD146Low -derived colonies, however, we found robust upregulation of the reporter gene, leading to 20.0±4.1 nGFP-positive cells per 5,000 plated cells at 7 days in culture. The number of nGFP expressing cells increased to 25.1±5.3 per 5,000 plated cells at 10 days and was 22.9±4.5 at 14 days (n = 8).

Hair cell-like cells.

a, Upregulation of nGFP in FACS-sorted non-sensory cell populations (n = 3–9). Color codes are indicated in Figs. 1 and 2. *** indicates p<0.0001. b, Expression of multiple hair cell markers in a subset of nGFP-positive hair cell-like cells. c, Merge of a light microscopic image with a fluorescent image showing 4 nGFP-positive cells in a colony derived from GFP-/CD271Low/CD326+/CD146Low cells. d, The same colony as in (c), visualized with SEM. e,f,g, Apical protrusions emanating from the cells labeled in (d) with e, f and g. The arrow points to the hair bundle-like protrusion in f. In g, the arrow points to a thicker protrusion, a presumptive kinocilium-like structure. h, Higher magnification image of a hair bundle-like protrusion.

Reporter gene upregulation is an indication that the nGFP-expressing cells are differentiating into hair cells, but to unequivocally identify them as hair cell-like cells we determined the co-expression of two additional hair cell markers, myosin VIIA and espin (Fig. 5b). 70.5±5.2% (n = 7) of nGFP-expressing cells that formed after 7 days in vitro in colonies from GFP−/CD271Low/CD326+/CD146Low cells coexpressed myosin VIIA. Likewise, 48.5±16.1% of the myosin VIIA and nGFP-positive cells also expressed the F-actin bundling protein espin, a marker for stereocilia29,30. Coexpression of nGFP with myosin VIIA in the GFP−/CD271Low/CD326+/CD146Low cell-derived colonies continued to increase at 10 and 14 days in vitro, whereas the fraction of myosin VIIA- and nGFP-positive cells that coexpressed espin remained unchanged. This result could be an indication that the culture conditions were sufficient to induce the differentiation of nascent hair cell-like cells, but that the conditions were insufficient to properly sustain survival of maturing hair cells.

This assessment was further supported by the forlorn shapes of the nascent hair bundles that protruded from nGFP-positive cells. We identified nGFP-expressing cells in GFP−/CD271Low/CD326+/CD146Low cell-derived colonies after 10 days in vitro and marked the positive colonies (Fig. 5c). We then fixed and processed the cells for scanning electron microscopy and identified the marked colonies (Fig. 5d). All hair bundle-like structures that we identified were irregular in shape, with fused stereocilia, protruding from cells that appeared to be loosely connected to their neighboring cells (Fig. 5e–g). Some hair bundles appeared in better shape with some tendency for acentric localization on the apical surface of hair cell-like cells. Some bundles appeared to have a thicker protrusion in the center of the tallest row of presumptive stereocilia, which could resemble a kinocilium (arrow in Fig. 5g). Generally, the hair bundle-like protrusions displayed the typical staircase architecture normally associated with sensory hair cells (Fig. 5h).

Previous reports showed that hair cell-like cells, derived from cochlear cell populations, differentiate either from proliferating progenitors or they develop by a phenotypical conversion from a differentiated supporting cell6,9. Because the colonies that grew from GFP−/CD271Low/CD326+/CD146Low cells were mostly EdU-positive, we hypothesized that most hair cell-like cells were derived from proliferating progenitor cells. To label hair cell-like cells generated from proliferating progenitor cells, we added EdU throughout the colony formation phase. We found that presence of EdU, even at very low concentration (1µM), strongly inhibited the occurrence of nGFP-positive cells in GFP−/CD271Low/CD326+/CD146Low cell-derived colonies. The thymidine analog BrdU had a similar detrimental effect, which we had reported previously6. We consequently restricted the time period in which EdU was present in the cultures to a 36h period at the beginning of the culture and we found EdU-positive hair cell-like cells when we analyzed the maturing colonies at day 10 (Fig. 6a). This finding, combined with the evidence that many colonies are derived from single or just a few proliferating cells (Fig. 4c), supports our conclusion that hair cell-like cells differentiate from progenitors that are derived from individual proliferating GFP−/CD271Low/CD326+/CD146Low cells.

Hair cell-like cells originate from proliferating and Sox2-positive cells.

a, EdU incorporation into hair cell-like cells after 10 days in vitro. b, Number of Sox2-expressing cells in FACS-sorted non-sensory cell populations (n = 3–6). Color codes are indicated in Figs. 1 and 2. * and *** indicate p<0.05 and p<0.001, respectively. c, Co-labeling for nGFP and Sox2 in colonies derived from GFP-/CD271Low/CD326+/CD146Low cells at 7 and 14 days in vitro. d, Fraction of nGFP expression of Sox2-positive cells in GFP−/CD271Low/CD326+/CD146Low colonies at 3, 7, 10 and 14 days in vitro, indicated in percent.

GFP−/CD271Low/CD326+/CD146Low-derived hair cell-bearing patches mature similar to inner ear sensory epithelium

Inner ear sensory hair cells and supporting cells arise from common progenitor cells. Hair cells are always associated with supporting cells, which express the transcription factor Sox2 that is required for sensory epithelial development and expressed in the vast majority of mouse inner ear supporting cells31,32. During inner ear development, Sox2 is expressed in prosensory cells that give rise to hair- and supporting cells and it becomes downregulated in nascent and maturing hair cells but remains expressed in supporting cells33. After 3 days in culture, Sox2-expressing cells were mainly detectable in colonies derived from GFP−/CD271Low/CD326+/CD146Low cells and increased steadily when assessed after 7, 10 and 14 days in vitro (Fig. 6b). The other inner ear-derived FACS-purified cell populations harbored only few Sox2-expressing cells, which did not increase significantly during the 14 days culture period.

In “young” GFP−/CD271Low/CD326+/CD146Low cell-derived colonies after 3 and 7 days in vitro, we found that many nGFP-positive nascent hair cell-like cells co-expressed Sox2, but usually with lower intensity than surrounding nGFP-negative cells (Fig. 6c). After 14 days in vitro, less than 10% of nGFP-expressing cells were Sox2-positive (Fig. 6c,d), suggesting that Sox2 is initially expressed in hair- and supporting cell progenitors and becomes downregulated in more mature hair cell-like cells as seen in native developing sensory epithelia34.

Discussion

In this study, we used antibodies to cell surface proteins to label dissociated cells of the neonatal organ of Corti and closely associated tissues. Cells that were differentially marked with these antibodies were sorted into four populations of non-sensory cells and one sensory hair cell population, which was identified by nGFP expression. Because our main interest was in ascertaining the regenerative potential of different cochlear non-sensory cell populations, we focused on the four non-sensory populations. Nevertheless, we also tested the survival and proliferation potential of sorted cochlear hair cells, represented by the GFP+ cell population and we found that dissociated hair cells were neither able to form colonies nor did they survive culturing on mitotically inactivated chicken utricle stromal feeder cells. Gene array analyses revealed that the four non-sensory populations were distinctively different from each other. Surprisingly, the cells that labeled with CD271 antibody to p75 neurotrophin receptor (GFP−/CD271High) consisted of a population of cells that were enriched for monocytes/macrophages and not the anticipated population of pillar and Hensen's cells. This conclusion was based on the results of our gene array analyses, which detected extremely high differential expression of monocyte and macrophage markers in this population, although this does not exclude the possibility that other cell types were also present. Absence of pillar and Hensen's cells in this population was further supported by differential upregulation of mRNA encoding p75 neurotrophin receptor in the GFP−/CD271Low/CD326+/CD146Low population when compared with the other populations. Thus, pillar and Hensen's cells were not present in the CD271High population, but were found in the cell population that presumably consisted of supporting cells and LER. The CD271 nonspecificity was unexpected because a previous study has used antibodies to p75 neurotrophin receptor for FACS sorting and has demonstrated by quantitative PCR that pillar and Hensen's cells are starkly enriched9. Differences in the enzymatic cell dissociation procedure or in primary and secondary antibody specificity are presumably the culprit for the unspecific labeling that we observed in our experiments. Nevertheless and despite this nonspecificity, CD271-labeled cells consisted of a defined cell population highly enriched for macrophage marker gene expression. Since macrophages can be found in the cochlea, particularly after damage11,12,35, we argue that these cells represent a valid group of cochlear cells and we decided to include them in our analysis. Because we suspect that pillar and Hensen's cells are present in the GFP−/CD271Low/CD326+/CD146Low population, one could argue that CD271 selection is not necessary for the present experimental procedure to purify the most potent regenerative cell population. Monocytes and macrophages in this case would likely be segregating to the CD326− cell population.

The three remaining groups of non-sensory cells were initially divided by differential CD326 labeling. Our immunohistological analysis confirmed a previous report that the CD326 antigen EpCAM is expressed in all cochlear epithelial cells10. Based on this expression pattern, we expected that CD326+ cells consist of epithelial cells of the organ of Corti and adjacent tissues, but not mesenchymal and nerve-associated cells located below the basilar membrane. Conversely, we hypothesized that the CD326− cell population would consist of cells located below the basilar membrane. Our gene array analysis supports this hypothesis. Within the CD326+ cell population, we further discriminated between cells that expressed higher levels of CD146 and cells that expressed lower levels of CD146. We excluded ≈2% of cells whose CD146 expression levels was mid-range, between the CD146High and the CD146Low population. Gene array analysis revealed that the CD146High and CD146Low populations were distinctively different. Markers for GER cells were upregulated in CD146High cells, whereas all markers that one would expect in organ of Corti supporting cells and the LER were highly expressed in the CD146Low population. Interestingly, both cell populations displayed proliferative potential in sphere and colony formation assays, but only CD146Low cells were able to generate sensory patches that robustly gave rise to hair- and supporting cell-like cells. This observation is consistent with previous reports describing the proliferative potential of GER and LER cells3,4.

Overall, it appears that many different cells of the mitotically quiescent P3 organ of Corti are able to re-enter the cell cycle and to mitotically proliferate after dissociation and culture at low densities. This proliferative capacity seems to be robust and has been validated several times3,4,5,6,7,9,36,37. Our data shows that GER cells have the greatest proliferative capacity, which appears to correlate with high levels of CD326 and CD146. Our results also show that the proliferative capacity and the ability to function as sensory epithelium progenitor cell are distinctively different features. GER cells, marked by expression of high levels of CD146, were able to proliferate into large colonies, but they rarely gave rise to hair- and supporting cell-like cells. The CD146Low population consisting of LER and supporting cells, however, was the only cell population derived from the P3 organ of Corti that was able to proliferate and to generate patches of epithelial cells that robustly gave rise to hair and supporting cell-like cells. With regard to the potential of GER cells to generate hair cell-like cells, it is interesting to note that postnatal ectopic expression of Atoh1 in GER cells leads to the differentiation of new hair cell-like cells38, which shows that these cells are certainly competent to differentiate into sensory epithelial cells. Likewise, coculture of GER-derived cells with mesenchymal cells resulted in upregulation of individual hair cell markers in some cells3, a result consistent with our interpretation that GER and also sub-basilar membrane cell populations harbor a few cells with capacity to give rise to hair and supporting cell-bearing epithelial patches. The most potent cell population with respect to hair cell and supporting cell generation, however, was defined by expression of CD326 and low levels of CD146.

Colonies derived from the CD326+/CD146Low population consisting of LER and supporting cells did not only express markers for hair cells and supporting cells, but also gave rise to hair cell marker-positive cells with hair bundle-like protrusions. SEM revealed that these hair cell-like cells were not well integrated into the epithelial patches and that the hair bundles were disorganized. Our serum-free culture conditions were obviously sufficient for de-differentiation, proliferation and colony formation, as well as differentiation into sensory patches, but we presume that maintenance of nascent hair cells and proper maturation will require different conditions. In fact, we observed a decrease of hair cell marker-expressing cells when we maintained the cultures with nGFP-positive cells beyond the 14 day differentiation period. This suggests that proper hair cell maturation and survival requires a switch to culture conditions optimized for maintaining in vitro-generated hair cell-like cells. Similar observations were made with embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cell-generated sensory patches29. On the other hand, the culture conditions used for colony generation were sufficient to establish prosensory cell clusters defined by expression of Sox2, increase of the number of Sox2-expressing cells, followed by downregulation of Sox2 in nascent hair cell-like cells identified by expression of nGFP(Atoh1). Downregulation of Sox2 in Atoh1-expressing nascent hair cells has been described as a permissive step for hair cell differentiation34. Observing a parallel process in LER/supporting cell-derived colonies suggests that the cells in these clusters undergo a process of prosensory cell differentiation that is similar to nascent development of inner ear sensory epithelia. It is interesting in this regard that Sox2 expression was initially high in the LER/supporting cell population, based on our gene array analysis, but Sox2 became downregulated after the cells were plated and then was upregulated in the differentiating epithelial patches. This pattern of disappearing and reappearing of developmentally expressed genes, combined with the proliferative capacity, suggest that these cells underwent a form of de-differentiation. The triggers for this de-differentiation, which does not happen in vivo, are likely to be found in cell dissociation, which leads to a proliferative response, for example, of adult mouse utricle supporting cells39. Growth factors are certainly augmenting this response7.

In conclusion, our study revealed that non-sensory cells of the neonatal organ of Corti and surrounding cochlear tissue have robust proliferative capacity when taken out of the context of the coherent epithelium. The different cell types, isolated by distinct surface markers, were able to de-differentiate and proliferate. The population consisting of LER and supporting cells displayed a stronger ability than other non-sensory cells to proliferate into colonies with nascent sensory patches. The identification of molecular markers that can be used to separate LER cells from supporting cells will be an important next step to further analyze the regenerative potential of different cell types of the cochlear epithelium.

Methods

Tissue preparation and cell sorting

Homozygous male Math1/nGFP mice in C57BL/6 genetic background expressing a nuclear variant of enhanced green fluorescent protein (nGFP) driven by an Atoh1 enhancer were crossed with CD-1 females to gain large litter size. The resultant Math1/nGFP heterozygous mice displayed uniform nGFP expression in all hair cells of the organ of Corti. Experiments were conducted under protocols approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Stanford University School of Medicine. Cochlear ducts were dissected free of stria vascularis and spiral ganglia and cleaned as carefully as possible from adjacent tissues. Enzymatic digestion was done with 0.5 mg/ml thermolysin for 20 min at 37°C, followed by a 6 min treatment with Accutase (Sigma). The digested tissue was triturated 10 times using 23G x 1 blunt aluminum needles (Monoject, Kendall) and one volume of DPBS (Invitrogen) with 10% FBS was added. The suspension was passed through a 40 μm cell strainer (BD Falcon) to remove clumps and cellular aggregates. All following steps were performed on ice in FACS buffer consisting of DPBS with 4% FBS. Cells were incubated for 25 min with fluorochrome-conjugated monoclonal mouse antibodies CD146 (1∶1000, PE, Biolegend, 134704) and CD326 (1∶1000, PE/Cy7, Biolegend, 118201) and with rabbit polyclonal CD271 primary antibody (1∶2000, Chemicon, AB1554). Thereafter cells were collected by centrifugation at 300 rcf for 5 min, washed once in FACS buffer and incubated for 25 min with secondary goat anti-rabbit antibody (1∶250, Jackson ImmunoResearch, 111-495-144). Cells were diluted 1∶28 with FACS buffer and propidium iodide (Sigma) was added at a final concentration of 1µg/ml to label nonviable cells. Cell viability of all experiments combined was 83.6±2.8% (n = 9). Cochleae from wild type CD-1 mice were used to determine background levels of labeling for every sort. FACS was performed with a BD FACSAria III flow cytometer using a 100 µm nozzle (BD Biosciences). Forward and side scattering was used to exclude debris and cell aggregates such as doublets.

Sphere formation

The cells were cultured at a density of 3 cells/μl in serum-free media consisting of DMEM/F12 (Gibco), supplemented with N2 and B27, bFGF (10 ng/ml), IGF-1 (50 ng/ml), EGF (20 ng/ml), heparan sulfate (50 ng/ml) and ampicillin (50 µg/ml; all from Sigma) in 96-well suspension culture plates (Greiner Bio-one). For proliferation assays EdU (Invitrogen) was present at 10 µM for a 36h period at the beginning of the culture. EdU was imaged using Click-iT labeling (Invitrogen) according to the instructions provided by the manufacturer.

Utricular stromal feeder cells

Cells were prepared from 20 embryonic day 15 chicken utricles whose sensory epithelia were removed after 40 min treatment with 0.5 mg/ml thermolysin (Sigma) in DMEM/F12 at 37°C. The pieces of stromal tissue were washed in PBS and transferred into a 150 μl drop of 0.125% trypsin/EDTA in PBS and incubated for 5 min at 37°C. After adding DMEM/F12 media supplemented with 10% FBS and 50 μg/ml ampicillin, the cells were gently triturated and cultured until 80%–90% confluence in a T75 flask. Cells were expanded in three passages before generating frozen stock of 106 cells per ml in DMEM/F12 with 20% FBS and 10% DMSO. After thawing and recovery of frozen stromal cells, they were plated into fibronectin-coated 4-well dishes (Greiner Bio-one) at 30,000 cells per ml and grown until 90% confluence. The cells were then mitotically inactivated with 2 μg/ml mitomycin C in DMEM/F12 with 5% FBS for 3hr, washed 3× in media and then used for otic cell differentiation.

Adherent colony formation assay and cell differentiation

5,000 FACS-sorted cells were plated into 4-well dishes containing mitotically inactivated chicken utricle stromal cell feeders and cultured in the same serum-free media as used for sphere formation for the first 3 days. 75% of the culture media was replaced with fresh media every 36h. After three days, cell differentiation was induced by switching to media lacking the growth factors. 75% of the culture media was replaced every 36h. In the colony proliferation assays EdU (10μM) was present for the first 3 days. To demonstrate EdU incorporation in nGFP positive cells, the EdU concentration was reduced to 1μM and was present only for the first 36h.

Immunocytochemistry

The cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 min at room temperature. Nonspecific binding sites were blocked for 1hr in 0.1% Triton X-100, 1% bovine serum albumin and 5% heat-inactivated goat serum in PBS. The fixed cells were incubated overnight at 4°C with diluted antibodies: 1∶1000 for monoclonal rat to Uvomorulin/E-cadherin (Sigma), 1∶300 for polyclonal goat antibody to Sox2 (Santa Cruz), 1∶1000 for polyclonal guinea pig antibody to myosin VIIa7, 1∶1000 for polyclonal rabbit antibody to espin40 and 1∶100 for monoclonal mouse antibody to hair cell antigen41. FITC-, TRITC- and Cy5-conjugated species and subtype-specific secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch) were used to detect primary antibodies. Nuclei were visualized with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Images were acquired with a Zeiss Axioimager fluorescence microscope.

Scanning electron microscopy

The cells were fixed for 4h with 2% glutaraldehyde / 4% paraformaldehyde with 50 mM CaCl2 and 20 mM MgCl2 in 0.1M HEPES buffer (pH = 7.4), post-fixed with 1% aqueous OsO4, dehydrated in a graded ethanol series and finally dried by critical point drying with liquid CO2 (Autosamdri-815 from Tousimis, Rockville, MD). Specimens were sputter-coated with 100Å Au/Pd using a Denton Desk II Sputter Coater and viewed with a Hitachi S-3400N variable pressure SEM operated under high vacuum at 5–10 kV at a working distance of 7–10 mm. Chemicals were supplied by Electron Microscopy Sciences (Hatfield, PA).

Data presentation and statistics

Acquired images were imported into Photoshop (CS5, Adobe), resized and cropped, if needed. The dynamic ranges of each individual RGB channel as a whole were adjusted using the Photoshop Levels function. Data are presented as mean values ± S.E.M. The number of biological replicate of completely independent experiments are indicated with “n”. Two-tailed unpaired Student's t-tests were conducted with Aabel 3 (Gigawiz).

References

Brigande, J. V. & Heller, S. Quo vadis hair cell regeneration? Nat Neurosci 12, 679–685 (2009).

Stone, J. S. & Cotanche, D. A. Hair cell regeneration in the avian auditory epithelium. Int J Dev Biol 51, 633–647 (2007).

Zhang, Y. et al. Isolation, growth and differentiation of hair cell progenitors from the newborn rat cochlear greater epithelial ridge. J Neurosci Methods 164, 271–279 (2007).

Zhai, S. et al. Isolation and culture of hair cell progenitors from postnatal rat cochleae. J Neurobiol 65, 282–293 (2005).

Malgrange, B. et al. Proliferative generation of mammalian auditory hair cells in culture. Mech Dev 112, 79–88 (2002).

Diensthuber, M., Oshima, K. & Heller, S. Stem/progenitor cells derived from the cochlear sensory epithelium give rise to spheres with distinct morphologies and features. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 10, 173–190 (2009).

Oshima, K. et al. Differential distribution of stem cells in the auditory and vestibular organs of the inner ear. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 8, 18–31 (2007).

Senn, P., Oshima, K., Teo, D., Grimm, C. & Heller, S. Robust postmortem survival of murine vestibular and cochlear stem cells. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 8, 194–204 (2007).

White, P. M., Doetzlhofer, A., Lee, Y. S., Groves, A. K. & Segil, N. Mammalian cochlear supporting cells can divide and trans-differentiate into hair cells. Nature 441, 984–987 (2006).

Hertzano, R. et al. CD44 is a marker for the outer pillar cells in the early postnatal mouse inner ear. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 11, 407–418 (2010).

Hirose, K., Discolo, C. M., Keasler, J. R. & Ransohoff, R. Mononuclear phagocytes migrate into the murine cochlea after acoustic trauma. J Comp Neurol 489, 180–194 (2005).

Jabba, S. V. et al. Macrophage invasion contributes to degeneration of stria vascularis in Pendred syndrome mouse model. BMC Med 4, 37 (2006).

Hwang, C. H. et al. Role of bone morphogenetic proteins on cochlear hair cell formation: analyses of Noggin and Bmp2 mutant mice. Dev Dyn 239, 505–513 (2010).

Burton, Q., Cole, L. K., Mulheisen, M., Chang, W. & Wu, D. K. The role of Pax2 in mouse inner ear development. Dev Biol 272, 161–175 (2004).

Hayashi, T., Cunningham, D. & Bermingham-McDonogh, O. Loss of Fgfr3 leads to excess hair cell development in the mouse organ of Corti. Dev Dyn 236, 525–533 (2007).

Bermingham-McDonogh, O. et al. Expression of Prox1 during mouse cochlear development. J Comp Neurol 496, 172–186 (2006).

Romand, R. et al. Spatio-temporal distribution of cellular retinoid binding protein gene transcripts in the developing and the adult cochlea. Morphological and functional consequences in CRABP- and CRBPI-null mutant mice. Eur J Neurosci 12, 2793–2804 (2000).

Pauley, S., Lai, E. & Fritzsch, B. Foxg1 is required for morphogenesis and histogenesis of the mammalian inner ear. Dev Dyn 235, 2470–2482 (2006).

Luo, J., Wang, H., Lin, J. & Redies, C. Cadherin expression in the developing chicken cochlea. Dev Dyn 236, 2331–2337 (2007).

Lopez, I. A., Ishiyama, G., Lee, M., Baloh, R. W. & Ishiyama, A. Immunohistochemical localization of aquaporins in the human inner ear. Cell Tissue Res 328, 453–460 (2007).

Sawada, S. et al. Aquaporin-1 (AQP1) is expressed in the stria vascularis of rat cochlea. Hear Res 181, 15–19 (2003).

Hurley, P. A., Crook, J. M. & Shepherd, R. K. Schwann cells revert to non-myelinating phenotypes in the deafened rat cochlea. Eur J Neurosci 26, 1813–1821 (2007).

Rendtorff, N. D., Frodin, M., Attie-Bitach, T., Vekemans, M. & Tommerup, N. Identification and characterization of an inner ear-expressed human melanoma inhibitory activity (MIA)-like gene (MIAL) with a frequent polymorphism that abolishes translation. Genomics 71, 40–52 (2001).

Gritti, A. et al. Multipotential stem cells from the adult mouse brain proliferate and self-renew in response to basic fibroblast growth factor. J Neurosci 16, 1091–1100 (1996).

Kalani, M. Y. et al. Wnt-mediated self-renewal of neural stem/progenitor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105, 16970–16975 (2008).

Reynolds, B. A. & Rietze, R. L. Neural stem cells and neurospheres--re-evaluating the relationship. Nat Methods 2, 333–336 (2005).

McKay, R. Stem cells in the central nervous system. Science 276, 66–71 (1997).

Lumpkin, E. A. et al. Math1-driven GFP expression in the developing nervous system of transgenic mice. Gene Expr Patterns 3, 389–395 (2003).

Oshima, K. et al. Mechanosensitive hair cell-like cells from embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell 141, 704–716 (2010).

Zheng, L. et al. The deaf jerker mouse has a mutation in the gene encoding the espin actin-bundling proteins of hair cell stereocilia and lacks espins. Cell 102, 377–385 (2000).

Oesterle, E., Campbell, S., Taylor, R., Forge, A. & Hume, C. in ARO Midwinter Meeting.

Kiernan, A. E. et al. Sox2 is required for sensory organ development in the mammalian inner ear. Nature 434, 1031–1035 (2005).

Hume, C. R., Bratt, D. L. & Oesterle, E. C. Expression of LHX3 and SOX2 during mouse inner ear development. Gene Expr Patterns 7, 798–807 (2007).

Dabdoub, A. et al. Sox2 signaling in prosensory domain specification and subsequent hair cell differentiation in the developing cochlea. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105, 18396–18401 (2008).

Sato, E., Shick, H. E., Ransohoff, R. M. & Hirose, K. Expression of fractalkine receptor CX3CR1 on cochlear macrophages influences survival of hair cells following ototoxic injury. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 11, 223–234 (2010).

Savary, E. et al. Cochlear stem/progenitor cells from a postnatal cochlea respond to Jagged1 and demonstrate that notch signaling promotes sphere formation and sensory potential. Mech Dev 125, 674–686 (2008).

Savary, E. et al. Distinct population of hair cell progenitors can be isolated from the postnatal mouse cochlea using side population analysis. Stem Cells 25, 332–339 (2007).

Zheng, J. L. & Gao, W. Q. Overexpression of Math1 induces robust production of extra hair cells in postnatal rat inner ears. Nat Neurosci 3, 580–586 (2000).

Li, H., Liu, H. & Heller, S. Pluripotent stem cells from the adult mouse inner ear. Nat Med 9, 1293–1299 (2003).

Li, H. et al. Correlation of expression of the actin filament-bundling protein espin with stereociliary bundle formation in the developing inner ear. J Comp Neurol 468, 125–134 (2004).

Richardson, G. P., Bartolami, S. & Russell, I. J. Identification of a 275-kD protein associated with the apical surfaces of sensory hair cells in the avian inner ear. J Cell Biol 110, 1055–1066 (1990).

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of our laboratory for critically reading the manuscript. J. Johnson (UT Southwestern) for Math1/nGFP mice and L. Joubert (Stanford EM core facility) for expert assistance with electron microscopy. Giovanni Coppola (UCLA) for excellent help with gene array experiments and Chad Tang (Stanford) for help with flow cytometry. This project was supported by the Sigrid Jusélius Foundation (S.T.S), the Instrumentarium Science Foundation (S.T.S), HHMI medical student fellowship (T.A.J.), K08 DC011043 (A.G.C.), as well as grants DC006167, DC010042 and P30 DC010363 from the National Institutes of Health to S.H.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

STS and SH conceived the study and wrote the manuscript. STS, SH, TAJ, BHH, AGC and KO participated in study design. STS, RL and KO conducted the experiments shown in Figs. 1a,b. STS, RC, TAJ, RL, FG, WS and KO conducted the experiments shown in Figs. 1c, 4, 5 and 6. STS, RL and BHH conducted the experiments shown in Figs. 1d and 2. AGC prepared Fig. 3. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Sinkkonen, S., Chai, R., Jan, T. et al. Intrinsic regenerative potential of murine cochlear supporting cells. Sci Rep 1, 26 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00026

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00026

This article is cited by

-

AAV-Net1 facilitates the trans-differentiation of supporting cells into hair cells in the murine cochlea

Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences (2023)

-

Transcriptomic and epigenomic analyses explore the potential role of H3K4me3 in neomycin-induced cochlear Lgr5+ progenitor cell regeneration of hair cells

Human Cell (2022)

-

Age-related transcriptome changes in Sox2+ supporting cells in the mouse cochlea

Stem Cell Research & Therapy (2019)

-

Molecular characterization and prospective isolation of human fetal cochlear hair cell progenitors

Nature Communications (2018)

-

ATOH1/RFX1/RFX3 transcription factors facilitate the differentiation and characterisation of inner ear hair cell-like cells from patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells harbouring A8344G mutation of mitochondrial DNA

Cell Death & Disease (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.