Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive and incurable neurodegenerative disorder clinically characterized by cognitive decline involving loss of memory, reasoning and linguistic ability. The amyloid cascade hypothesis holds that mismetabolism and aggregation of neurotoxic amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides, which are deposited as amyloid plaques, are the central etiological events in AD. Recent evidence from AD mouse models suggests that blood-borne mononuclear phagocytes are capable of infiltrating the brain and restricting β-amyloid plaques, thereby limiting disease progression. These observations raise at least three key questions: (1) what is the cell of origin for macrophages in the AD brain, (2) do blood-borne macrophages impact the pathophysiology of AD and (3) could these enigmatic cells be therapeutically targeted to curb cerebral amyloidosis and thereby slow disease progression? This review begins with a historical perspective of peripheral mononuclear phagocytes in AD, and moves on to critically consider the controversy surrounding their identity as distinct from brain-resident microglia and their potential impact on AD pathology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the leading cause of dementia in elderly populations throughout the world. With human longevity increasing, AD prevalence is predicted to place enormous strain on the public health system. Deposition of amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides [proteolytically derived from the ~110 kDa amyloid precursor protein (APP)] as β-amyloid plaques within the brain is a defining feature of the disease (Selkoe 2001). This age-dependent, insidious deposition of β-amyloid is purported to cause an “amyloid cascade”, which results in a vicious feed-forward cycle, culminating in neuronal death and dementia (Hardy and Allsop 1991; Tanzi and Bertram 2005). A cure, effective treatment, or preventative therapy for AD does not exist. Yet, a number of studies in AD patients and in transgenic mouse models of the disease have recently shown immune cell infiltrates around Aβ plaques. Collectively, these studies raise the tantalizing possibility that a subset of bone marrow-derived mononuclear phagocytes are capable of entering the brain and potentially restricting cerebral amyloid.

During embryogenesis, hematopoietic myeloid cells migrate into the brain and differentiate into microglia, the resident central nervous system (CNS) macrophages (Eglitis and Mezey 1997; Brazelton et al. 2000; Mezey et al. 2000). Microglia continuously survey the CNS for debris and foreign antigens, and thereby serve as a first line of immune defense in the brain and spinal cord. In the AD brain and in transgenic AD mouse models, microglia become activated in response to Aβ deposits, and proliferate and migrate to sites containing amyloid plaques (Simard et al. 2006). In addition to these brain-resident macrophages (referred to as microglia in this review), a subset of innate immune cells also exist that are products of pluripotent hematopoietic monocyte precursors. The contribution of bone marrow-derived mononuclear phagocytes (used interchangeably with the term “peripheral macrophages” in this review) to amyloid plaque-associated microgliosis is still under debate, but is likely limited (Wyss-Coray 2006; Jücker and Heppner 2008). This is because the potentially damaging effects of an inflammatory immune response within the CNS are sanctioned by the blood–brain barrier (BBB), which restricts passage of substances and blood-borne cells (e.g., peripheral leukocytes) into the brain (Wenkel et al. 2000).

Although the CNS has classically been regarded as an immune privileged site, recent evidence indicates that surveillance by peripheral leukocytes occurs both physiologically and during disease. It should be noted that peripheral leukocyte traffic into the healthy CNS remains a subject of debate, particularly with regard to surveillance T cells. Although brain penetration of these cells is a quantitatively minor event, we nonetheless often detect CD4+ T cells in the brain parenchyma of unmanipulated healthy wild-type mice (see Fig. 1). Yet, given that peripheral immune cells are present in such small quantity within the CNS, there is discussion over whether targeting them would have a beneficial or detrimental impact on disease. This debate may be moot when considering that peripheral leukocytes can serve either productive or pathological roles depending on the specific CNS disease (for a review, see Rezai-Zadeh et al. 2009b). For example, exogenous leukocytes have been shown to be pathogenic in diseases such as experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (an animal model for the human demyelinating disease multiple sclerosis) (Fujinami and Oldstone 1985; Greter et al. 2005), Parkinson’s disease (Czlonkowska et al. 2002; Whitton 2007) and human immunodeficiency virus encephalitis (Petito et al. 2006; Liu et al. 2009). On the other hand, infiltrating lymphocytes can serve to limit neuronal loss in models of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Beers et al. 2008; Chiu et al. 2008). Additionally, recent evidence from mouse models supports the notion that infiltration of peripheral mononuclear phagocytes limits progression of AD pathology (Town et al. 2008) and militates against West Nile virus encephalitis (Town et al. 2009). In the context of AD and other neuroinflammatory diseases, a critical understanding of the role of subpopulations of microglia/macrophages is required to stimulate the right cell type to eliminate toxic Aβ and prevent neuronal damage without bystander injury associated with neuroinflammation. Brain recruitment of exogenous leukocytes is an intriguing strategy by which to protect and regenerate the CNS (Yong and Rivest 2009). However, a thorough understanding of the cellular and molecular mechanisms responsible for trafficking of peripheral macrophages in AD is crucial to efficiently coax these cells out of the circulation and into the brain. In this article, we review (1) the role of mononuclear phagocytes in the pathoetiology and potential treatment of AD, (2) recent evidence that points to a “blood-borne identity” of these cells, and (3) controversies surrounding phenotypic distinction of these cells from brain-intrinsic microglia.

A historical perspective

The longstanding debate surrounding the role of microglia/macrophages in AD was initially ignited by landmark studies in the late 1980s and early 1990s by Henryk Wisniewski and Janusz Frackowiak. Wisniewski and Frackowiak observed that microglia, while capable of engulfing Aβ in vitro, were not competent Aβ phagocytes in vivo. Using electron microscopy to examine the ultrastructure of these enigmatic cells, Wisniewski noted that microglial cells associated with Aβ plaques in AD patient brains did not contain Aβ deposits within lysosomal compartments. However, in the rare comorbidity of stroke with AD, brain-infiltrating macrophages did contain lysosomal β-amyloid fibrils (Wisniewski et al. 1989; Wisniewski et al. 1991; Frackowiak et al. 1992). These observations led to the conclusion that, while microglia did not have the ability to clear Aβ from the extracellular brain milieu, peripheral macrophages could “home” to and remove Aβ in vivo by phagocytosis.

As with any important and thought-provoking work, Wisniewski’s results sparked numerous questions. Was there a true disparity between microglia and peripheral macrophages regarding Aβ clearance? Were infiltrating macrophages capable of limiting cerebral amyloidosis? Why were infiltrating macrophages restricted from the AD brain in the absence of stroke comorbidity? Answering these questions would prove difficult due to a number of obstacles. For instance, aside from morphological differences, distinguishing between activated microglia and macrophages can be complex as they share many of the same cell surface receptors and signaling proteins. In fact, despite the enlightening observations by Wisniewski et al., it would take nearly two decades for availability of modern cellular and molecular biology techniques to address the conditions under which peripheral macrophages were capable of removing brain Aβ.

The origin and role of mononuclear phagocytes in the central nervous system

Around the time of Wisniewski’s observations, it was understood that the CNS contained two distinct populations of mononuclear phagocytes: the microglial cells of the brain parenchyma and the macrophages that reside in perivascular spaces, meningeal folds, and the choroid plexus. These two classes of phagocytes are known to differ in the production of specific cytokines, cell surface immune antigen expression, and ability to promote innate versus adaptive immune responses. Despite these phenotypic differences, there is mounting evidence that both classes of mononuclear phagocytes share a common precursor. Microglia are thought to originate from the yolk sac during embryogenesis, when macrophage progenitors (of blood-borne monocytic origin) also exist. It is now generally accepted that microglia originate from monocyte precursor cells that migrate from the yolk sac into the developing CNS (Pessac et al. 2001; Alliot et al. 1999). Furthermore, it is generally thought that populations of microglia arise and are maintained entirely through local CNS proliferation (Ajami et al. 2007; Mildner et al. 2007). This conclusion has been challenged, though, by important work demonstrating that blood-borne monocyte progenitors can replenish pools of parenchymal blood-borne macrophages and CNS-resident microglia (Priller et al. 2001)—although this seems to only occur to a limited extent.

Discrete populations of exogenous, blood-borne monocytes are now believed to be recruited to the CNS, where they traverse the BBB (primarily at post-capillary venules), both normally and after CNS injury or disease. The fate of these immune cells depends largely on the route taken to brain infiltration. First, monocytes may only superficially penetrate into the brain, and remain as perivascular macrophages that are functionally distinct from brain-resident microglia (Hawkes and McLaurin 2009). These cells may migrate across the vascular wall where they enter the perivascular space, meninges, or choroid plexus and differentiate into tissue macrophages that closely resemble brain-resident microglia. Finally, monocytes may progress through the glia limitans (a network of astrocyte foot processes) into the brain parenchyma and assume a bona fide microglial phenotype. In a pioneering study, Priller et al. demonstrated that hematopoietic cells are indeed capable of entering the CNS and differentiating into microglia. Utilizing irradiation chimeras in which donor hematopoietic cells were genetically modified with a retroviral vector encoding green fluorescent protein (GFP), these researchers showed that marrow-derived cells are capable of entering into the CNS and differentiating into cells phenotypically resembling microglia. Additionally, these GFP+ microglia were found at sites of CNS damage, underscoring the ability of blood-borne mononuclear cells to migrate to sites of neuronal injury.

However, reports by Ajami, Mildner, and their colleagues have raised methodological concerns about studies touting peripheral macrophage engraftment into the brain after irradiation and bone marrow reconstitution. In an elegant study, Ajami et al. used parabiosis (where the circulatory systems of syngeneic mice are physically connected) to generate chimeric animals. These parabiosis experiments were conducted in parallel with conventional irradiation/transplantation chimeras. Surprisingly, these authors only found significant engraftment of GFP+ mononuclear cells in the CNS following irradiation (Ajami et al. 2007). In another study, Mildner et al. demonstrated that head-sparring irradiation resulted in relative exclusion of marrow-derived GFP+ mononuclear cells from the brain parenchyma compared with conventional irradiation chimeras (Mildner et al. 2007). These reports suggest that full-body irradiation, by itself, causes damage to the BBB that allows blood-borne mononuclear cells to more readily traffic to and infiltrate both the healthy and injured CNS. Furthermore, these authors concluded that local self-renewal of microglia is sufficient to sustain brain-resident mononuclear phagocyte populations, which they suggest account for the bulk of CNS innate immune responses.

Yet, others have challenged that the studies by Ajami and Mildner have their own technical limitations. For example, the parabiosis model employed by Ajami et al. has recently been found to underestimate constitutive infiltration of mononuclear cells into lymphoid tissues (Liu et al. 2007). In addition, Mildner et al. did not detect transplanted GFP+ brain perivascular macrophages following head-sparring irradiation and bone marrow reconstitution, which is a well-established resident macrophage subset. In light of these experimental pitfalls, the origin and role of mononuclear phagocytes in CNS innate immunity still remains to be fully elucidated.

Distinguishing between brain-resident microglia and peripheral macrophages

The ability to distinguish cell type (microglia vs. monocytes/macrophages) and provenance (CNS-resident vs. blood-borne) of mononuclear phagocytes is critically important in determining the functional roles of these cells. As mentioned above, microglia and peripheral monocytes/macrophages are phenotypically different and may also display varying degrees of functional restriction. Accordingly, differences in immunological/molecular marker expression, morphological states, and functional characteristics may be evaluated to discriminate between these cellular subsets. In particular, quiescent microglia are morphologically characterized by a small soma and ramified processes, whereas, resting monocytes/macrophages are rounded, oval, or amoeboid. However, the utility of relying on morphological features to distinguish these cell types is likely limited. For one, morphological assessment, by its very nature, is qualitative. Further, a rapid phenotype switch may occur after microglial activation, whereby cells shorten their cellular processes and swell their soma, thereby assuming an amoeboid morphology similar to peripheral macrophages. Moreover, while resting macrophages are characterized by constitutive expression of specific cell surface immune antigens including major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II, CD45, CD64, CD68, CD86, and F4/80 antigen, microglia can be induced to express these same markers following activation (Flaris et al. 1993; Stoll and Jander 1999; Walker 1999). However, CD45 expression on peripheral macrophages is generally accepted to be higher than on activated microglia (Juedes and Ruddle 2001), and so researchers often utilize flow cytometry to distinguish between these two populations.

Functionally, resting populations of peripheral macrophages may be differentiated from populations of resting microglia by constitutive secretion of interferon-γ (IFN-γ); however, one group reported that the source of “macrophage” IFN-γ production was actually emanating from contaminating natural killer cells (Schleicher et al. 2005). While these conventional means of discerning the identity of mononuclear phagocytes are useful, they may not be adequate for determining cellular lineage. In this regard, expression levels of specific immunological markers such as CD45, Ly-6C, Ly-6G, and the chemokine receptor CCR2 on mononuclear phagocytes and their progenitors may be relied upon, as these markers are reportedly present when these cells migrate into the CNS (Drevets et al. 2004; Sunderkotter et al. 2004; El Khoury et al. 2007; King et al. 2009). We recently utilized CD11c as a marker to distinguish peripheral macrophages (which express this surface antigen) from brain-resident microglia (which are CD11c-negative) (Town et al. 2008). Because we did not detect CD11c expression by β-amyloid plaque-associated microglia, we concluded that the low-level, chronic inflammation that characterizes AD is not powerful enough to elicit expression of this marker by brain-resident microglia (which are constitutively negative for CD11c; see Town et al. 2008). Possibly, CD11c expression by brain-resident microglia requires strong, acute activation (for example, in cases of CNS autoimmune disease such as multiple sclerosis), and immunostimulation in the context of AD is simply not vigorous enough. Altogether, these various approaches for distinguishing mononuclear phagocyte subsets have proven useful, but are nonetheless limited as the ultimate phenotype and fate of these cells after migration into the brain remains indeterminate.

Why target peripheral macrophages rather than brain-resident microglia?

Wisniewski’s early findings prompted an intriguing question: what makes peripheral macrophages more adept than brain-resident microglia at phagocytosing Aβ in vivo? There are several characteristics of peripheral macrophages that make them efficient professional Aβ phagocytes. First, monocyte precursors that develop into peripheral macrophages have a dynamic life cycle, while brain-resident microglia have a prolonged lifespan and limited capacity to divide (Graeber et al. 1992; Kennedy and Abkowitz 1998). Further, it has been suggested that peripheral macrophages can enter and exit the CNS compartment throughout life (Dickson 1999). In contrast, microglia are permanent CNS residents, and their phenotype is significantly influenced by habitation there (Dickson 1999). Brain-resident microglia are therefore more tightly regulated spatially and temporally, allowing for precise CNS-tuned immune responses but restricted functional repertoire. In their quiescent (resting) state, human brain-resident microglia in general lack MHC-II (HLA-DR) antigen, cytokine expression, CD45 antigen, and other surface immune molecules required for antigen presentation and phagocytosis. Alternatively, peripheral mononuclear phagocytes constitutively express HLA-DR and are capable of the full repertoire of innate immune responses. Thus, while microglia serve as sentinels to disruption of homeostasis in neural tissue and have limited innate immune responses, peripheral mononuclear phagocytes are unrestricted in their abilities to engulf and digest cellular debris and pathogens.

Given that peripheral macrophages originate from monocyte progenitors present in the bone marrow and the circulation, these cells can be therapeutically targeted in a minimally invasive fashion in the periphery (Rezai-Zadeh et al. 2009a). Conversely, targeting brain-resident microglia for therapeutics can be challenging due to the presence of the BBB (Rezai-Zadeh et al. 2009b). Moreover, given the fact that peripheral macrophages are generally regarded as professional phagocytes, they have greater Aβ phagocytic potential than their immune-repressed microglia cousins. Consequently, although brain-resident microglia and peripheral macrophages share the same lineage, their phagocytic properties are strongly determined by the microenvironment in which they reside.

Yet, a conspicuous and important question is whether the provenance of the mononuclear phagocyte has functional implications in the context of AD pathology. A recent report from the laboratory of Mathias Jücker has prompted the iconoclastic conclusion that resident microglia don’t play any significant role in Aβ clearance (Grathwohl et al. 2009). These researchers utilized a novel “suicide gene” transgenic mouse model, which expresses the herpes simplex virus (HSV) thymidine kinase (TK) gene under regulatory control of the myeloid-specific CD11b promoter (termed CD11b-HSVTK mice). In principle, when these mice are treated with the antiviral nucleotide analog prodrug ganciclovir (GCV), HSVTK (the suicide gene portion of the system) converts the drug into a toxic triphosphate. Thus, GCV treatment leads to selective ablation of proliferating myeloid cells. After selectively ablating brain-resident microglia in the APPPS1 transgenic mouse model of AD, they found no effect on overall Aβ burden, plaque morphology, or distribution of cerebral Aβ deposits. Additionally, these authors did not detect altered neural dystrophy in these mice, suggesting that brain-resident microglia are neither pathogenic nor remedial in regards to Aβ-driven neurotoxicity (Grathwohl et al. 2009).

These data further enforce the notion that microglia are poor Aβ phagocytes and do not significantly remodel Aβ plaques. However, others have challenged that this report does not address the effect of GCV treatment on various subsets of CD11b+ cells in these mice, and that the short time-course of microglial ablation (only a few weeks) begs the question of whether these results are truly definitive. Other critiques are that this report does not address the percentage of ablation of the wide range of CD11b-expressing cells of monocytic lineage nor whether subsets are varyingly capable of restricting Aβ burden. Moreover, vascular toxicity and breakdown associated with GCV treatment may complicate interpretation of these results. Nonetheless, at face-value, these data imply that brain-resident microglia are incapable of (1) phagocytosing/clearing Aβ from the parenchyma and (2) impacting neuronal injury. If these results translate to the clinic, they reinforce the notion that peripheral mononuclear phagocytes are a better pharmacological target for Aβ clearance than brain-resident microglia.

Yet, a recent report by Kiyota et al. has shed light on the actions of microglia in the context of AD. These researchers crossed a transgenic mouse model over-expressing chemokine (C–C motif) ligand 2 (CCL2) with the Tg2576 Alzheimer’s model. They reported that forced expression of CCL2 enhanced microgliosis and induced diffuse amyloid plaque deposition in Tg2576 mice. The authors’ interpretation was that CCL2 and tumor necrosis factor-α directly facilitated Aβ uptake, intracellular Aβ oligomerization, and protein secretion (Kiyota et al. 2009). Therefore, while it is becoming accepted that microglia are not potent Aβ clearing cells, their ability to remodel Aβ plaques and contribute to AD pathology requires further delineation.

Are infiltrating macrophages beneficial or detrimental in AD?

The idea that the peripheral immune system could play a beneficial role in mitigating AD pathology was initially met with controversy and resistance. Early studies questioned whether: (1) blood-borne immune cells could be manipulated to effectively traverse the BBB; (2) invasion of peripheral immune cells into the brain would result in beneficial phagocytosis of Aβ deposits; and (3) such cells would provoke deleterious brain inflammation and cause tissue damage. The idea that blood-borne immune cells might drive damaging brain inflammation is reasonable, as a variety of CNS diseases earmarked by presence of immune cell infiltrates are often accompanied by severe inflammation and neuronal bystander injury.

In order to address whether bone marrow-derived cells were capable of entering the CNS in response to Aβ, Stalder et al. generated a chimeric mouse model of AD in which bone marrow-derived cells (but not resident microglia) were selectively marked by GFP. In their model, brain amyloid deposits triggered invasion of peripheral macrophages. Importantly, GFP+ peripheral macrophages were much more likely to be found in the brain (associated with amyloid) in mice expressing the APP23 transgene than in wild-type animals (Stalder et al. 2005). However, only a small subpopulation (less than 20%) of plaques were associated with infiltrating macrophages, which called into question the magnitude of peripheral macrophage entry into the brain and the ability of these brain-invading cells to respond to and/or clear Aβ deposits. Moreover, the modest number of macrophage-associated Aβ plaques implied a brain-inhibitory mechanism or an intrinsic peripheral macrophage defect in response to Aβ. Although the passage of peripheral mononuclear phagocytes into the CNS seems limited, Serge Rivest’s group demonstrated that bone marrow-derived cells that do succeed in traversing the BBB display higher levels of proteins associated with antigen presentation than resident microglia (Simard et al. 2006). These researchers utilized the aforementioned transgenic mouse that expresses the TK protein under the control of the CD11b promoter to demonstrate that peripheral macrophages and not brain-resident microglia have the ability to clear Aβ by a phagocytic mechanism. However, the model used included intracerebroventricular injections and irradiation, both of which potentially disrupt BBB integrity. Thus, the question of whether disruption of the BBB is necessary for Aβ phagocytic activity of invading macrophages still remains controversial (Massengale et al. 2005). Nonetheless, the findings of Simard et al. (2006) suggest that peripheral immune cells may be more efficient Aβ phagocytes than resident microglia.

Two recent studies in mice indicate that, though limited, the recruitment of blood-borne macrophages to Aβ plaques plays an important role. Joseph El Khoury and colleagues crossed an AD mouse model with a strain that lacks the CC-chemokine receptor 2 (Ccr2) gene. Interestingly, Ccr2 deficient mice displayed impaired trafficking of peripheral macrophages and resident microglia to Aβ plaques. More importantly, however, this diminished recruitment of mononuclear phagocytes was associated with increased Aβ plaque load and accelerated mortality (El Khoury et al. 2007). Additional studies by Michal Schwartz and colleagues provide further evidence for the importance of peripheral macrophages in Aβ plaque clearance. After first observing that T cell based immunization augmented clearance of Aβ plaques by increasing the density of local CD11c+ dendritic-like cells (Butovsky et al. 2006), they subsequently showed that this effect could be abrogated by selective ablation of bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (Butovsky et al. 2007). These studies further indicate that brain invasion of peripheral immune cells may play an important role in reducing Aβ burden and associated cognitive impairment. However, more work needs to be done to understand mechanisms of blood-borne phagocyte recruitment to the brain before we can design effective therapeutic strategies to coax these cells across the BBB.

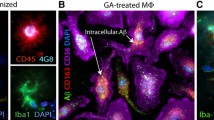

Recent studies by our group illuminated a novel approach to this problem. We found that interruption of transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) and downstream Smad2/3 signaling (TGF-β-Smad2/3) in innate immune cells in a mouse model of AD significantly diminished cerebral amyloid burden and partially remediated behavioral impairment (Town et al. 2008). Importantly, this effect was associated with recruitment of blood-borne macrophages to Aβ deposits, and further in vitro mechanistic investigation revealed that peripheral macrophages, but not microglia, displayed increased Aβ phagocytosis in this scenario. Furthermore, these brain-infiltrating macrophages resembled a subset of peripheral mononuclear phagocytes shown to display an anti-inflammatory (Ly-6C−) profile (Sunderkotter et al. 2004; Geissmann et al. 2003). Thus, our results show that removing immunosuppressive TGF-β signaling from blood-borne macrophages effectively recruits these cells to brain amyloid deposits. Importantly, this beneficial response on restricting cerebral amyloid does not come at the cost of increased brain inflammation, since these animals had increased brain interleukin (IL)-10 mRNA abundance. If these results translate to the clinical syndrome, then these peripheral phagocytes may be therapeutically targeted for both anti-inflammatory and pro-Aβ phagocytic outcomes (Town et al. 2008; Town 2009).

Peripheral macrophages may not necessarily need to cross the BBB to exert beneficial effects on AD. Up to 86% of human AD cases present with cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) (Ellis et al. 1996), characterized by deposition of Aβ in cerebral vessels (Jellinger and Attems 2008). Importantly, CAA severity correlates with degree of dementia in humans (Attems et al. 2005), although there has been much debate about whether CAA is a driving force in the pathobiology of AD. Yet, CAA may represent an important therapeutic target in AD. Recently, Hawkes and McLaurin showed that a perivascular subset of peripheral macrophages are important for clearance of CAA (Hawkes and McLaurin 2009). They observed that macrophage-depleted TgCRND8 mice exhibited significantly more evidence of cerebral vascular Aβ deposits (comprised of the more toxic Aβ42 peptide) compared to vehicle controls. This group further noted that stimulating peripheral mononuclear phagocyte turnover via chitin treatment resolved CAA, an effect that appeared to be specifically mediated by peripheral mononuclear phagocytes as opposed to activated microglia or reactive astrocytes. Thus, this previously underappreciated perivascular macrophage subset may hold therapeutic potential for efficient clearance of vascular Aβ deposits.

Can pro-inflammatory macrophages be beneficial in AD?

Blood-borne mononuclear cells consist of heterogeneous populations of effector macrophages. It is now generally accepted that at least two effector macrophage subsets can be classified based on functional differences. The so-called M1 macrophages are short-lived and are thought to be actively recruited to inflamed tissues, where they elicit pro-inflammatory innate immune responses. Alternately, M2 macrophages are recruited to non-inflamed tissues and are believed to be highly phagocytic, anti-inflammatory effector cells (Geissmann et al. 2003; Rauh et al. 2005; Colton 2009). Although initially thought to be epiphenomenon, it is now generally accepted that neuroinflammation is intimately involved in the pathogenesis of AD. For this reason, anti-inflammatory strategies have been touted as potential therapeutic interventions for AD. Along these lines, our studies have demonstrated that infiltrating anti-inflammatory (M2-like) cells facilitate Aβ clearance (Town et al. 2008). However, it remains to be determined if all types of neuroinflammatory responses are inherently detrimental in neurodegenerative diseases including AD; some forms of brain inflammation may actually be beneficial.

The significance of this hypothesis is accentuated by recent studies, which showed that sustained recruitment of peripheral immune cells across the BBB was not only associated with neuroinflammation, but actually decreased cerebral amyloid burden (Shaftel et al. 2007a; Shaftel et al. 2007b). Using the IL-1βXAT transgenic mouse model, Shaftel et al. forced expression of IL-1β in the hippocampus, and observed persistent infiltration of diverse leukocyte populations. Importantly, this sustained invasion of peripheral immune cells did not evoke overt neurotoxicity. Shaftel et al. then crossed transgenic IL-1βXAT mice with the Alzheimer’s APP/PS1 mouse model, thereby triggering unilateral overexpression of IL-1β in the hippocampus and driving sustained neuroinflammation in an AD mouse model. Surprisingly, this neuroinflammatory response resulted in reduced cerebral amyloid pathology. The proposed mechanism for this result was that a subpopulation of mononuclear phagocytes was recruited to amyloid plaques and cleared them. This response seems to have been driven by bone marrow-derived macrophages, and one interpretation of their findings is that a strong brain inflammatory response induces infiltration of peripheral M1-like mononuclear cells that restrict cerebral amyloidosis.

A recent report by Pritam Das and coworkers further elucidated the beneficial role of a pro-inflammatory response in the context of AD. These researchers utilized a mouse model in which the murine form of the pleiotropic proinflammatory cytokine IL-6 (mIL-6) was overexpressed in brains of AD model mice, including TgCRND8 and Tg2576 animals. IL-6 has been purported to have a pathogenic role in AD because it is upregulated in the plasma, cerebrospinal fluid, and brain parenchyma of AD patients and is expressed at Aβ plaques (Licastro et al. 2000; Huell et al. 1995). As predicted, murine IL-6 expression promoted widespread gliosis in these AD mouse models. What was completely unexpected was that overexpression of this pro-inflammatory cytokine reduced Aβ deposition in TgCRND8 mice. Further, the researchers noted significant up-regulation of glial phagocytic markers in vivo and an increase in microglia-mediated phagocytosis of Aβ aggregates in vitro. Murine IL-6 expression did not affect APP processing in TgCRND8 mice, nor were differences detected in APP processing or steady-state levels of Aβ in young Tg2576 animals (Chakrabarty et al. 2010). Although the contribution of peripheral, bone marrow-derived macrophages to Aβ clearance was not specifically investigated, these data further suggest that at least this particular form of microglial activation may be beneficial by enhancing Aβ plaque clearance. These results are accentuated by a recent report by Boissonneault et al., who demonstrated that systemic macrophage colony-stimulating factor administration is a powerful treatment to stimulate bone marrow-derived microglia, degrade Aβ and prevent cognitive decline associated with cerebral amyloidosis in the Alzheimer’s APP/PS1 mouse model (Boissonneault et al. 2009). However, one must not overlook the potentially devastating effects of runaway brain inflammation in the context of AD. This is underscored by recent suspension of the Elan/Wyeth AN-1792 Aβ immunotherapy trial, which resulted in life-threatning adverse events including severe brain inflammation (aseptic meningoencephalitis) in ~6% of treated patients (Nicoll et al. 2003; Town et al. 2005; Holmes et al. 2008).

Concluding remarks

Over two decades ago, Henryk Wisniewski made a seminal observation. He found that, while brain-resident microglia were “frustrated phagocytes” that were unable to clear cerebral amyloid; blood-borne macrophages present in the brain parenchyma of stroke patients with AD had Aβ clearance aptitude. It would take over 20 years and the advent of modern cellular and molecular biology for us to begin to understand this innate immune cell dichotomy (Fig. 2). Even so, we have only just begun to address questions surrounding these enigmatic cells. For example, which subset(s) of peripheral mononuclear phagocytes are most efficient at clearing cerebral amyloid? How do we target these professional phagocytes to remove Aβ without incurring bystander injury associated with inflammation? On the translational medicine front, we are just now exploring genetic and pharmacologic strategies to promote brain entry of peripheral mononuclear phagocytes with the goal of restricting cerebral amyloid. The 5-year view looks promising as we invest in answering these and other tantalizing questions about this potentially promising cell type to target for the treatment of AD.

A schematic representation showing the roles of mononuclear phagocytes in Alzheimer’s disease. A penetrating cerebral artery is shown on the left, and a β-amyloid plaque within the brain parenchyma is shown to the right. Peripheral mononuclear phagocytes (macrophages) are infiltrating the brain parenchyma and homing to the β-amyloid plaque, where they phagocytose and clear deposited Aβ. Peripheral mononuclear phagocytes are depicted in green, brain-resident microglia are magenta, neurons are blue, and the β-amyloid plaque is shown in red

References

Ajami B, Bennett JL, Krieger C, Tetzlaff W, Rossi FM (2007) Local self-renewal can sustain CNS microglia maintenance and function throughout adult life. Nat Neurosci 10(12):1538–1543

Alliot F, Godin I, Pessac B (1999) Microglia derive from progenitors, originating from the yolk sac, and which proliferate in the brain. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 117(2):145–152

Attems J, Jellinger KA, Lintner F (2005) Alzheimer’s disease pathology influences severity and topographical distribution of cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Acta Neuropathol 110(3):222–231

Beers DR, Henkel JS, Zhao W, Wang J, Appel SH (2008) CD4+ T cells support glial neuroprotection, slow disease progression, and modify glial morphology in an animal model of inherited ALS. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105(40):15558–15563

Boissonneault V, Filali M, Lessard M, Relton J, Wong G, Rivest S (2009) Powerful beneficial effects of macrophage colony-stimulating factor on beta-amyloid deposition and cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 132(4):1078–1092

Brazelton TR, Rossi FM, Keshet GI, Blau HM (2000) From marrow to brain: expression of neuronal phenotypes in adult mice. Science 290(5497):1775–1779

Butovsky O, Koronyo-Hamaoui M, Kunis G, Ophir E, Landa G, Cohen H, Schwartz M (2006) Glatiramer acetate fights against Alzheimer’s disease by inducing dendritic-like microglia expressing insulin-like growth factor 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103(31):11784–11789

Butovsky O, Kunis G, Koronyo-Hamaoui M, Schwartz M (2007) Selective ablation of bone marrow-derived dendritic cells increases amyloid plaques in a mouse Alzheimer’s disease model. Eur J Neurosci 26(2):413–416

Chakrabarty P, Jansen-West K, Beccard A, Ceballos-Diaz C, Levites Y, Verbeeck C, Zubair AC, Dickson D, Golde TE, Das P (2010) Massive gliosis induced by interleukin-6 suppresses Abeta deposition in vivo: evidence against inflammation as a driving force for amyloid deposition. FASEB J 24(2):548–559

Chiu IM, Chen A, Zheng Y, Kosaras B, Tsiftsoglou SA, Vartanian TK, Brown RH Jr, Carroll MC (2008) T lymphocytes potentiate endogenous neuroprotective inflammation in a mouse model of ALS. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105(46):17913–17918

Colton CA (2009) Heterogeneity of microglial activation in the innate immune response in the brain. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 4(4):399–418

Czlonkowska A, Kurkowska-Jastrzebska I, Czlonkowski A, Peter D, Stefano GB (2002) Immune processes in the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease—a potential role for microglia and nitric oxide. Med Sci Monit 8(8):RA165–RA177

Dickson DW (1999) Microglia in Alzheimer’s disease and transgenic models. How close the fit? Am J Pathol 154(6):1627–1631

Drevets DA, Dillon MJ, Schawang JS, Van Rooijen N, Ehrchen J, Sunderkotter C, Leenen PJ (2004) The Ly-6Chigh monocyte subpopulation transports Listeria monocytogenes into the brain during systemic infection of mice. J Immunol 172(7):4418–4424

Eglitis MA, Mezey E (1997) Hematopoietic cells differentiate into both microglia and macroglia in the brains of adult mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94(8):4080–4085

El Khoury J, Toft M, Hickman SE, Means TK, Terada K, Geula C, Luster AD (2007) Ccr2 deficiency impairs microglial accumulation and accelerates progression of Alzheimer-like disease. Nat Med 13(4):432–438

Ellis RJ, Olichney JM, Thal LJ, Mirra SS, Morris JC, Beekly D, Heyman A (1996) Cerebral amyloid angiopathy in the brains of patients with Alzheimer’s disease: the CERAD experience, Part XV. Neurology 46(6):1592–1596

Flaris NA, Densmore TL, Molleston MC, Hickey WF (1993) Characterization of microglia and macrophages in the central nervous system of rats: definition of the differential expression of molecules using standard and novel monoclonal antibodies in normal CNS and in four models of parenchymal reaction. Glia 7(1):34–40

Frackowiak J, Wisniewski HM, Wegiel J, Merz GS, Iqbal K, Wang KC (1992) Ultrastructure of the microglia that phagocytose amyloid and the microglia that produce beta-amyloid fibrils. Acta Neuropathol 84(3):225–233

Fujinami RS, Oldstone MB (1985) Amino acid homology between the encephalitogenic site of myelin basic protein and virus: mechanism for autoimmunity. Science 230(4729):1043–1045

Geissmann F, Jung S, Littman DR (2003) Blood monocytes consist of two principal subsets with distinct migratory properties. Immunity 19(1):71–82

Graeber MB, Streit WJ, Buringer D, Sparks DL, Kreutzberg GW (1992) Ultrastructural location of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II positive perivascular cells in histologically normal human brain. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 51(3):303–311

Grathwohl SA, Kalin RE, Bolmont T, Prokop S, Winkelmann G, Kaeser SA, Odenthal J, Radde R, Eldh T, Gandy S et al (2009) Formation and maintenance of Alzheimer’s disease beta-amyloid plaques in the absence of microglia. Nat Neurosci 12(11):1361–1363

Greter M, Heppner FL, Lemos MP, Odermatt BM, Goebels N, Laufer T, Noelle RJ, Becher B (2005) Dendritic cells permit immune invasion of the CNS in an animal model of multiple sclerosis. Nat Med 11(3):328–334

Hardy J, Allsop D (1991) Amyloid deposition as the central event in the aetiology of Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Pharmacol Sci 12(10):383–388

Hawkes CA, McLaurin J (2009) Selective targeting of perivascular macrophages for clearance of beta-amyloid in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106(4):1261–1266

Holmes C, Boche D, Wilkinson D, Yadegarfar G, Hopkins V, Bayer A, Jones RW, Bullock R, Love S, Neal JW et al (2008) Long-term effects of Abeta42 immunisation in Alzheimer’s disease: follow-up of a randomised, placebo-controlled phase I trial. Lancet 372(9634):216–223

Huell M, Strauss S, Volk B, Berger M, Bauer J (1995) Interleukin-6 is present in early stages of plaque formation and is restricted to the brains of Alzheimer’s disease patients. Acta Neuropathol 89(6):544–551

Jellinger KA, Attems J (2008) Cerebral amyloid angiopathy in Lewy body disease. J Neural Transm 115(3):473–482

Jücker M, Heppner FL (2008) Cerebral and peripheral amyloid phagocytes—an old liaison with a new twist. Neuron 59(1):8–10

Juedes AE, Ruddle NH (2001) Resident and infiltrating central nervous system APCs regulate the emergence and resolution of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol 166(8):5168–5175

Kennedy DW, Abkowitz JL (1998) Mature monocytic cells enter tissues and engraft. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95(25):14944–14949

King IL, Dickendesher TL, Segal BM (2009) Circulating Ly-6C+ myeloid precursors migrate to the CNS and play a pathogenic role during autoimmune demyelinating disease. Blood 113(14):3190–3197

Kiyota T, Yamamoto M, Xiong H, Lambert MP, Klein WL et al (2009) CCL2 accelerates microglia-mediated Aβ oligomer formation and progression of neurocognitive dysfunction. PLoS ONE 4(7):e6197

Licastro F, Pedrini S, Caputo L, Annoni G, Davis LJ, Ferri C, Casadei V, Grimaldi LM (2000) Increased plasma levels of interleukin-1, interleukin-6 and alpha-1-antichymotrypsin in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: peripheral inflammation or signals from the brain? J Neuroimmunol 103(1):97–102

Liu K, Waskow C, Liu X, Yao K, Hoh J, Nussenzweig M (2007) Origin of dendritic cells in peripheral lymphoid organs of mice. Nat Immunol 8(6):578–583

Liu J, Gong N, Huang X, Reynolds AD, Mosley RL, Gendelman HE (2009) Neuromodulatory activities of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in a murine model of HIV-1-associated neurodegeneration. J Immunol 182(6):3855–3865

Massengale M, Wagers AJ, Vogel H, Weissman IL (2005) Hematopoietic cells maintain hematopoietic fates upon entering the brain. J Exp Med 201(10):1579–1589

Mezey E, Chandross KJ, Harta G, Maki RA, McKercher SR (2000) Turning blood into brain: cells bearing neuronal antigens generated in vivo from bone marrow. Science 290(5497):1779–1782

Mildner A, Schmidt H, Nitsche M, Merkler D, Hanisch UK, Mack M, Heikenwalder M, Bruck W, Priller J, Prinz M (2007) Microglia in the adult brain arise from Ly-6ChiCCR2+ monocytes only under defined host conditions. Nat Neurosci 10(12):1544–1553

Nicoll JA, Wilkinson D, Holmes C, Steart P, Markham H, Weller RO (2003) Neuropathology of human Alzheimer disease after immunization with amyloid-beta peptide: a case report. Nat Med 9(4):448–452

Pessac B, Godin I, Alliot F (2001) Microglia: origin and development. Bull Acad Natl Med 185(2):337–346 (discussion 346–337)

Petito CK, Torres-Munoz JE, Zielger F, McCarthy M (2006) Brain CD8+ and cytotoxic T lymphocytes are associated with, and may be specific for, human immunodeficiency virus type 1 encephalitis in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J Neurovirol 12(4):272–283

Priller J, Flugel A, Wehner T, Boentert M, Haas CA, Prinz M, Fernandez-Klett F, Prass K, Bechmann I, de Boer BA et al (2001) Targeting gene-modified hematopoietic cells to the central nervous system: use of green fluorescent protein uncovers microglial engraftment. Nat Med 7(12):1356–1361

Rauh MJ, Ho V, Pereira C, Sham A, Sly LM, Lam V, Huxham L, Minchinton AI, Mui A, Krystal G (2005) SHIP represses the generation of alternatively activated macrophages. Immunity 23(4):361–374

Rezai-Zadeh K, Gate D, Szekely CA, Town T (2009a) Can peripheral leukocytes be used as Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers? Expert Rev Neurother 9(11):1623–1633

Rezai-Zadeh K, Gate D, Town T (2009b) CNS infiltration of peripheral immune cells: D-Day for neurodegenerative disease? J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 4(4):462–475

Schleicher U, Hesse A, Bogdan C (2005) Minute numbers of contaminant CD8+ T cells or CD11b+CD11c+ NK cells are the source of IFN-gamma in IL-12/IL-18-stimulated mouse macrophage populations. Blood 105(3):1319–1328

Selkoe DJ (2001) Alzheimer’s disease: genes, proteins, and therapy. Physiol Rev 81(2):741–766

Shaftel SS, Carlson TJ, Olschowka JA, Kyrkanides S, Matousek SB, O’Banion MK (2007a) Chronic interleukin-1 beta expression in mouse brain leads to leukocyte infiltration and neutrophil-independent blood brain barrier permeability without overt neurodegeneration. J Neurosci 27(35):9301–9309

Shaftel SS, Kyrkanides S, Olschowka JA, Miller JN, Johnson RE, O’Banion MK (2007b) Sustained hippocampal IL-1 beta overexpression mediates chronic neuroinflammation and ameliorates Alzheimer plaque pathology. J Clin Invest 117(6):1595–1604

Simard AR, Soulet D, Gowing G, Julien JP, Rivest S (2006) Bone marrow-derived microglia play a critical role in restricting senile plaque formation in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 49(4):489–502

Stalder AK, Ermini F, Bondolfi L, Krenger W, Burbach GJ, Deller T, Coomaraswamy J, Staufenbiel M, Landmann R, Jucker M (2005) Invasion of hematopoietic cells into the brain of amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice. J Neurosci 25(48):11125–11132

Stoll G, Jander S (1999) The role of microglia and macrophages in the pathophysiology of the CNS. Prog Neurobiol 58(3):233–247

Sunderkotter C, Nikolic T, Dillon MJ, Van Rooijen N, Stehling M, Drevets DA, Leenen PJ (2004) Subpopulations of mouse blood monocytes differ in maturation stage and inflammatory response. J Immunol 172(7):4410–4417

Tanzi RE, Bertram L (2005) Twenty years of the Alzheimer’s disease amyloid hypothesis: a genetic perspective. Cell 120(4):545–555

Town T (2009) Alternative Abeta immunotherapy approaches for Alzheimer’s disease. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 8(2):114–127

Town T, Tan J, Flavell RA, Mullan M (2005) T-cells in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuromolecular Med 7(3):255–264

Town T, Laouar Y, Pittenger C, Mori T, Szekely CA, Tan J, Duman RS, Flavell RA (2008) Blocking TGF-beta-Smad2/3 innate immune signaling mitigates Alzheimer-like pathology. Nat Med 14(6):681–687

Town T, Bai F, Wang T, Kaplan AT, Qian F, Montgomery RR, Anderson JF, Flavell RA, Fikrig E (2009) Toll-like receptor 7 mitigates lethal West Nile encephalitis via interleukin 23-dependent immune cell infiltration and homing. Immunity 30(2):242–253

Walker WS (1999) Separate precursor cells for macrophages and microglia in mouse brain: immunophenotypic and immunoregulatory properties of the progeny. J Neuroimmunol 94(1–2):127–133

Wenkel H, Streilein JW, Young MJ (2000) Systemic immune deviation in the brain that does not depend on the integrity of the blood–brain barrier. J Immunol 164(10):5125–5131

Whitton PS (2007) Inflammation as a causative factor in the aetiology of Parkinson’s disease. Br J Pharmacol 150(8):963–976

Wisniewski HM, Wegiel J, Wang KC, Kujawa M, Lach B (1989) Ultrastructural studies of the cells forming amyloid fibers in classical plaques. Can J Neurol Sci 16(4 Suppl):535–542

Wisniewski HM, Barcikowska M, Kida E (1991) Phagocytosis of beta/A4 amyloid fibrils of the neuritic neocortical plaques. Acta Neuropathol 81(5):588–590

Wyss-Coray T (2006) Inflammation in Alzheimer disease: driving force, bystander or beneficial response? Nat Med 12(9):1005–1015

Yong VW, Rivest S (2009) Taking advantage of the systemic immune system to cure brain diseases. Neuron 64(1):55–60

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by an NIA/NIH “Pathway to Independence” award (5R00AG029726-03 and 5R00AG029726-04). The authors would like to thank Jun Tan (University of South Florida), Gary E. Landreth (Case Western Reserve University), and Joseph El Khoury (Harvard Medical School) for helpful discussion and Pietro Martinez for assistance with the design and creation of Fig. 2. D.G. is supported by a donation from Gary and Cheryl Justice. T.T. is the inaugural holder of the Ben Winters Endowed Chair in Regenerative Medicine.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

D. Gate and K. Rezai-Zadeh contributed equally to this work.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Gate, D., Rezai-Zadeh, K., Jodry, D. et al. Macrophages in Alzheimer’s disease: the blood-borne identity. J Neural Transm 117, 961–970 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-010-0422-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-010-0422-7