Abstract

Reactive oxygen species regulate redox-signaling processes, but in excess they can cause cell damage, hence underlying the aetiology of several neurological diseases. Through its ability to down modulate reactive oxygen species, glutathione is considered an essential thiol-antioxidant derivative, yet under certain circumstances it is dispensable for cell growth and redox control. Here we show, by directing the biosynthesis of γ-glutamylcysteine—the immediate glutathione precursor—to mitochondria, that it efficiently detoxifies hydrogen peroxide and superoxide anion, regardless of cellular glutathione concentrations. Knocking down glutathione peroxidase-1 drastically increases superoxide anion in cells synthesizing mitochondrial γ-glutamylcysteine. In vitro, γ-glutamylcysteine is as efficient as glutathione in disposing of hydrogen peroxide by glutathione peroxidase-1. In primary neurons, endogenously synthesized γ-glutamylcysteine fully prevents apoptotic death in several neurotoxic paradigms and, in an in vivo mouse model of neurodegeneration, γ-glutamylcysteine protects against neuronal loss and motor impairment. Thus, γ-glutamylcysteine takes over the antioxidant and neuroprotective functions of glutathione by acting as glutathione peroxidase-1 cofactor.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

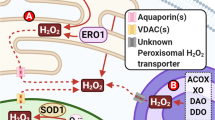

Mitochondria are both producers and targets of reactive oxygen species (ROS). A well-balanced equilibrium between mitochondrial ROS production and their elimination is critical for the control of redox-mediated cell signalling processes1. By disposing ROS, glutathione (γ-glutamylcysteinylglycine, GSH) is thought to be the main small thiol-antioxidant derivative2,3. GSH is synthesized exclusively in the cytosol in two consecutive ATP-requiring steps, the first of which, and rate limiting, being γ-glutamylcysteine formation by glutamate-cysteine ligase (GCL); glutathione synthetase (GSS) then forms the tripeptide by linking glycine to γ-glutamylcysteine2,3. It is well documented that pharmacological inhibition of GCL activity4 or knockdown of the catalytic GCL subunit5 increases ROS abundance, which mediates cellular damage; GCL genetic deletion is embryonically lethal6,7.

Interestingly, GSH is dispensable for the cell growth of Saccharomyces cerevisiae genetically deleted of GSS8. In addition, it has been recently demonstrated that, in S. cerevisiase devoid of GSS, GSH is essential for iron–sulfur cluster assembly, but not for thiol-redox control9. Both in yeast8 and in human fibroblasts10, genetic GSS deletion results in γ-glutamylcysteine accumulation; thus the antioxidant function of GSH might be adopted by γ-glutamylcysteine. Here we tested whether—and if so, how—γ-glutamylcysteine detoxifies hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and superoxide anion (O2·–) under intact, physiological GSH concentrations. To do so, GCL was directed to mitochondria, as this organelle cannot further transform γ-glutamylcysteine into GSH due to the absence of GSS11. We found that both mitochondrial-targeted newly synthesized, and endogenous γ-glutamylcysteine, efficiently dispose H2O2 by acting as glutathione peroxidase-1 cofactor. These results indicate that γ-glutamylcysteine is an important player in cellular redox control.

Results

Targeting functional GCL to mitochondria decreases ROS

To direct γ-glutamylcysteine synthesis to mitochondria, the full-length complementary DNA encoding the catalytic GCL subunit was fused with the mitochondrial-targeting signal of ornithine transcarbamylase. When expressed in HEK293T cells, this construct (mitoGCL) yielded a GCL protein that was confined to mitochondria and absent in the cytosol, as revealed by western blotting after cellular fractionation (Fig. 1a) and confocal microscopy (Fig. 1b). In contrast, expression of untagged GCL was exclusively present in the cytosol (Fig. 1a,b). Whole-cell extracts expressing mitoGCL revealed a super-shifted anti-GCL (1:1,000) band that was not present in the untagged GCL-expressing cells or in the mitoGCL-transfected mitochondria (Fig. 1c), suggesting that only the mitochondrial-targeting epitope-processed form of the protein was present in the mitochondrial fraction.

(a) Expression of GCL fused with the mitochondrial epitope of ornithine transcarbamylase (mitoGCL) in HEK293T cells shows localization in the mitochondrial, not in the cytosolic fraction, as judged by western blotting. Native (untagged) GCL is exclusively expressed in cytosol. (b) Confocal images show co-localization of mitoGCL with the mitochondrial marker mitoDsRed, whereas native GCL showed typical cytosolic diffused pattern. Cells nuclei were stained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Scale bar, 10 μm. (c) Whole extracts of cells expressing mitoGCL shows both native and mitochondrial-tagged GCL, as judged by the loss of the super-shifted band in the mitochondrial fraction. (d) mitoGCL is functional, as judged by the presence of GCL activity (synthesis of γ-glutamylcysteine, γGC) in the mitochondrial fraction (left panel); mitochondrial GSH concentration was unaltered by mitoGCL expression, whereas the rate of H2O2 production(AmplexRed), after treatment with 10 μM rotenone, significantly decreased (right panel). (e) Expression of the wild-type (mitoGCL) and the E103A inactive mutant form of mitoGCL showed identical protein abundance. (f) The E103A mutant mitoGCL form is inactive (left panel), as judged by the lack of γGC formation in transfected cells; rotenone (1 μM per 4 h) induced an increase in mitochondrial superoxide anion (O2·–) abundance, as revealed by MitoSox fluorescence detection followed by flow cytometry; this increase was partially prevented by the wild-type, but not by the E103A mutant inactive mitoGCL form (right panel). Mitochondrial enrichment was assessed by VDAC (Voltage Dependent Anion Channel) immunoblotting. The cytosolic enzyme GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) was used to assess equal loading in immunoblots. ND, not detected; *P<0.05 (analysis of variance; n=3 independent experiments). All data are expressed as mean±S.E.M±.

Then, we assessed whether expressed mitoGCL yielded functional GCL within mitochondria. As shown in Fig. 1d (left panel), GCL activity was undetectable in mitochondria isolated from control cells, but present in mitoGCL-transfected cells. Furthermore, neither mitochondrial (Fig. 1d, middle panel) nor cytosolic (Supplementary Fig. S1a) GSH concentrations changed by mitoGCL expression. Interestingly, H2O2 detection was significantly diminished by mitoGCL expression, as measured both in mitochondria (Fig. 1d, right panel) and in intact cells (Supplementary Fig. S1b,c). Expression of mitoGCL prevented the conversion of GSH to its oxidized form (GSSG) caused by rotenone (Supplementary Fig. S1d). To confirm that GCL activity wholly accounted for ROS down-modulation, we expressed (Fig. 1e) a E103A mutant12, inactive (Fig. 1f, left panel) form of mitoGCL. We found that rotenone-induced mitochondrial O2·– was significantly decreased by wild-type mitoGCL, but not by the E103A inactive form (Fig. 1f, right panel). These data confirm that γ-glutamylcysteine is required for the observed antioxidant function.

γ-Glutamylcysteine is a GPx1 cofactor that detoxifies H2O2

To decipher how γ-glutamylcysteine detoxified ROS but otherwise avoiding the influence of cytosolic GCL, we expressed a silent mutant mitoGCL form (mitoGCL (mut)) refractory to the action of a small hairpin RNA against GCL (shGCL)5, in HEK293T cells (Fig. 2a). Knocking down GCL markedly reduced total cellular GSH in both mitoGCL and mitoGCL (mut) transfected cells (Supplementary Fig. S1e). GCL knockdown was insufficient to trigger a significant increase in mitochondrial O2·–, but this was strongly potentiated by rotenone and rescued by mitoGCL (mut; Fig. 2b). Thus, in unstressed HEK293T cells, γ-glutamylcysteine may not contribute to the basal O2·– regulation that can occur in primary neurons, in which we previously reported a significant increase in O2·– by shGCL13. It therefore appears that the impact of γ-glutamylcysteine as a physiological redox regulator differs among cell types. Next, we knocked down GSS (Fig. 2c), which resulted in endogenous γ-glutamylcysteine accumulation and GSH decrease (Supplementary Table S1). We found that GSS knockdown abolished the increase in rotenone-induced O2·–, both in the absence (Supplementary Fig. S1f) and in the presence of mitoGCL (Fig. 2d).

(a) Expression of an shRNA against GCL (shGCL) in HEK293T cells efficiently knockdowns wild-type mitoGCL, but not a mutant form of mitoGCL (mitoGCL (mut)) that is refractory to shGCL. (b) Treatment of cells with rotenone (1 μM; 4 h) increased mitochondrial O2·–, as revealed by MitoSox fluorescence; this was further enhanced by GCL silencing (shGCL), and rescued by mitoGCL (mut) expression; GCL silencing in the absence of rotenone did not significantly modify mitochondrial O2·– in HEK293T cells (c) Western blots showing the efficacy of siRNA duplexes, used at 100 nM for 3 days in HEK293T cells, against glutathione synthetase (GSS), glutathione peroxidase-1 (GPx1), glutathione reductase (GSR) and superoxide dismutase-2 (SOD2); control siRNA (siControl) was an siRNA against luciferase. GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) was used as loading control. (d) Rotenone (1 μM; 4 h) increased mitochondrial O2·–, as judged by MitoSox fluorescence, in mitoGCL-expressing cells; this effect was abolished by GSS silencing and enhanced by GPx1 knockdown; silencing GSS did not rescue the increase in O2·– caused by GPx1 knockdown; GSR silencing did not alter, and SOD2 silencing enhanced rotenone-induced ROS. (e) γ-Glutamylcysteine (γGC) or GSH dose-dependently disposed H2O2 in vitro, but the presence of GPx1 (0.5 U ml−1) in the incubation medium was necessary for H2O2 disposal, as judged by the lack of effect of 500 μM γGC or GSH in the absence of GPx1 (w/o GPx1). (f) H2O2 disposal by GPx1 was not potentiated by the presence of GSR (0.5 U ml−1) in the incubation medium when γGC (200 μM) was used (left panel); however, the presence of GSH (200 μM) potentiated GPx1-mediated H2O2 disposal (right panel). *P<0.05; #P<0.05 versus siControl (mitoGCL; analysis of variance; n=3 independent experiments); in vitro assays (e and f) were performed in sextuplicate. All data are expressed as mean±S.E.M.

We then sought to elucidate if γ-glutamylcysteine served as a glutathione peroxidase cofactor. As glutathione peroxidase-1 (GPx1) largely accounts for mitochondrial H2O2 detoxification14, we knocked down it (Fig. 2c), which resulted in a significant enhancement of rotenone-induced O2·– (Fig. 2d). Furthermore, GSS knockdown was unable to decrease O2·– levels during GPx1 silencing (Fig. 2d). The oxidized form of γ-glutamylcysteine was undetectable in cultured cells (Supplementary Table S1), but it was present in all tissues analysed in vivo (brain, liver and kidney; Supplementary Table S2). Knocking down glutathione reductase (GSR) failed to enhance rotenone-induced O2·– (Fig. 2d). To disregard a direct interaction of γ-glutamylcysteine with O2·–, we silenced the mitochondrial isoform of superoxide dismutase (SOD2; Fig. 2c), which enhanced rotenone-induced O2·– (Fig. 2d). The ability of either γ-glutamylcysteine or its cognate cofactor, GSH, to dispose H2O2 in vitro was then assessed in the absence or presence of purified GPx1. As shown in Fig. 2e, γ-glutamylcysteine and GSH were unable to detoxify H2O2, unless GPx1 was present; γ-glutamylcysteine dose-dependently accelerated GPx1-mediated H2O2 disposal at a similar efficiency to that by GSH, at least at low concentrations of the thiols (Fig. 2e). GSR failed to improve the GPx1-dependent ability of γ-glutamylcysteine, but not that of GSH, at disposing H2O2 (Fig. 2f). We also tested the ability of γ-glutamylcysteine to induce protein modification, which was found to be well below that of GSH (Supplementary Table S3).

mitoGCL decreases ROS in neurons and is neuroprotective

Neurons are particularly vulnerable against excess ROS, hence requiring continuous supply and regeneration of GSH for survival15. We therefore investigated the possible efficacy of γ-glutamylcysteine at detoxifying ROS in (patho) physiologically relevant neuronal death models. Glutamate treatment increased mitochondrial O2·– in rat primary neurons (Fig. 3a; Supplementary Fig. S2a), an effect that was abolished by the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist16, MK801 (Supplementary Fig. S2b). Expression of mitoGCL in neurons was sufficient to decrease basal mitochondrial O2·– (Fig. 3a), which contrasts with the lack of effect in HEK293T cells (Fig. 1f). The different response of these cells to mitoGCL expression is likely due to the above-mentioned vulnerability of neurons to oxidative stress15 versus the resistance of HEK293T cells (Fig. 2b). Furthermore, mitoGCL, but not its inactive E103A mutant form, prevented the increase in mitochondrial O2·– induced by glutamate-receptor stimulation (Fig. 3a). GPx1—but not GSS or GSR—knockdown (Supplementary Fig. S2c) significantly enhanced O2·– (Fig. 3b), despite neurons expressed mitoGCL, indicating that GPx1 use of γ-glutamylcysteine is essential for γ-glutamylcysteine-mediated O2·– detoxification in this model of excitotoxicity. Glutamate triggered an increase in the proportion of neurons with active caspase-3 (Fig. 3c) and with annexin V+/7-AAD− staining (Fig. 3d), indicating an intrinsic (mitochondrial) mode of apoptotic death; this was prevented by antagonizing the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (Supplementary Fig. S2d,e). Notably, mitoGCL largely—but not fully—prevented the rise in the percentage of neurons with the apoptotic phenotype (Fig. 3c,d). In addition, mitoGCL abolished O2·– enhancement triggered by other mitochondrial ROS-inducing agents17,18, such as rotenone, antimycin and 3-nitropropionic acid (3NP; Fig. 3e).

(a) Transfection of rat primary neurons with mitoGCL, but not with its inactive form (mitoGCL (E103A)), significantly decreased basal levels of mitochondrial O2·–, as quantified by MitoSox fluorescence in the transfected neurons (identified by GFP+ fluorescence); mitoGCL—but not mitoGCL (mut)—fully prevented glutamate (100 μM per 5 min)-induced mitochondrial O2·–, as quantified 24 h after glutamate treatment, by MitoSox fluorescence. (b) Silencing glutathione peroxidase-1 (siGPx1), but not glutathione synthetase (siGSS) or glutathione reductase (siGSR), significantly enhanced glutamate (100 μM per 5 min)-mediated mitochondrial O2·–, as judged by MitoSox fluorescence 24 h after treatment, in mitoGCL-expressing neurons; such enhancement was not affected by GSS co-silencing. (c) Expression of mitoGCL rescued the increase, observed after 24 h, in active caspase-3 in GFP+-neurons triggered by glutamate (100 μM per 5 min), as assessed by flow cytometry. (d) mitoGCL expression prevented neuronal apoptotic death, as revealed by annexin V+/7-AAD− neurons 24 h after glutamate treatment (100 μM per 5 min). (e) mitoGCL expression prevented the increase in mitochondrial O2·– (as assessed by MitoSox fluorescence) caused by incubation of neurons with rotenone (Rot, 10 μM), antimycin A (AA, 10 μM) or 3-nitropropionic acid (3NP, 2 mM) for 15 min. NS, not significant; *P<0.05; #P<0.05 versus untreated (analysis of variance; n=3 independent culture preparations). All data are expressed as mean±S.E.M.

mitoGCL exerts neuroprotection in vivo

To confirm that γ-glutamylcysteine exerted neuroprotection in vivo, lentiviral particles expressing wild-type or inactive (E103A) mitoGCL were stereotaxically injected into the striatum of adult mice. After 3 days, striatal GCL activity was significantly higher in mice injected with mitoGCL than in those injected with inactive mitoGCL (E103A), whereas striatal GSH concentrations remained unchanged (Fig. 4a). After 3 days of lentiviral injections, mice were intraperitoneally injected with 3NP (seven doses of 50 mg kg−1, twice daily), a well-described model of neurodegeneration18. Indeed, we observed that 3NP treatment induced a significant increase in neuronal apoptotic death in the striatum, as judged by TdT-mediated dUTP nick end labelling assay, in the mice pre-injected with inactive mitoGCL (E103A), but not in those pre-injected with wild-type mitoGCL (Fig. 4b,c). Notably, there was a significant loss of striatal neurons in the mice pre-injected with the inactive mitoGCL (E103A), but not in those pre-injected with the wild-type mitoGCL (Fig. 4d; Supplementary Fig. S2f). Mice treated with vehicle instead of 3NP showed no neuronal loss, regardless of the isoform of mitoGCL (wild type or inactive) pre-injected (Fig. 4d; Supplementary Fig. S2f). To evaluate behavioural function, these mice were tested for motor coordination and balance. As shown in Fig. 4e, 3NP treatment induced a progressive motor impairment in the mice that were pre-injected with the inactive mitoGCL (E103A), but not in those pre-injected with the wild-type mitoGCL; mice treated with vehicle instead of 3NP showed no motor impairment, regardless of the isoform of mitoGCL (wild type or inactive) pre-injected (Fig. 4e).

(a) Lentiviral particles expressing wild-type or inactive (E103A) mitoGCL were stereotaxically injected (5×106 p.f.u. per 3 μl at 0.25 μl min−1) into the striatum of adult mice. After 3 days, striatal GCL activity was significantly higher in mice injected with mitoGCL than in those injected with inactive mitoGCL (E103A), whereas striatal GSH concentrations remained unchanged. (b) Confocal images of striatal sections showing neuronal apoptotic death. After 3 days of lentiviral particles injections, 3NP was intraperitoneally injected (seven doses of 50 mg kg−1, twice daily), which induced a significant increase in neuronal apoptotic death (TUNEL+/Neu+ cells) in the striatum, in the mice pre-injected with inactive mitoGCL (E103A), but not in those pre-injected with wild-type mitoGCL; scale bar, 20 μm. (c) This panel shows the quantitative data of b. (d) After 3 days of lentiviral particles injections, 3NP was intraperitoneally injected, which induced, 3 days later, a significant loss of striatal NeuN+ neurons only in the mice that received inactive mitoGCL (E103A), but not in those that received wild-type mitoGCL; mice treated with vehicle instead of 3NP showed no neuronal loss regardless of the isoform of mitoGCL (wild type or inactive) lentiviral particles injected; the quantitative analysis is shown. (e) After 3 days of lentiviral particles injections, 3NP was intraperitoneally injected, which induced, 3 days later, a progressive motor impairment (rotarod test) in mice pre-injected with inactive mitoGCL (E103A), but not with wild-type mitoGCL; mice treated with vehicle, instead of 3NP, showed no neuronal loss, regardless of the isoform of mitoGCL (wild type or inactive) pre-injected. *P<0.05; #P<0.05 versus all conditions on each day (Student's t-test for (a,c); n=3 mice; analysis of variance for (d,e); n=6–8 mice). TUNEL, TdT-mediated dUTP nick end labelling. All data are expressed as mean±S.E.M.

Discussion

Here we show that γ-glutamylcysteine is a thiol-redox regulator that efficiently detoxifies mitochondrial ROS. This was evidenced by confining γ-glutamylcysteine synthesis to mitochondria, which were unable to convert the newly synthesized γ-glutamylcysteine into GSH due to the lack of mitochondrial GSS11. Thus, down-modulation of mitochondrial ROS by γ-glutamylcysteine took place under physiological GSH concentrations. Furthermore, the robust antioxidant protection observed in intact GSS knockdown cells corroborates such a role by endogenous γ-glutamylcysteine. Notably, impairing γ-glutamylcysteine biosynthesis in the cytosol, but not in mitochondria, still allowed γ-glutamylcysteine to efficiently detoxify ROS. Together, these results indicate that the antioxidant action of γ-glutamylcysteine takes place regardless of GSH concentrations, thus cannot simply rely on its ability to replenish GSH, as it can be seen in other paradigms19.

Our results also reveal that GPx1 is an essential component in the detoxifying function of γ-glutamylcysteine. Furthermore, the occurrence of an oxidized form of γ-glutamylcysteine in all tissues analysed, in vivo, strongly suggests the notion of a γ-glutamylcysteine redox cycle. However, knocking down GSR—presumably required for an eventual regeneration of reduced γ-glutamylcysteine from its oxidized form—failed to enhance O2·–. The biochemical pathway responsible for the reduction of γ-glutamylcysteine from its oxidized form therefore remains to be elucidated. On the other hand, a putative function of γ-glutamylcysteine as direct superoxide anion scavenger is disregarded, as SOD2 knockdown could not further enhance rotenone-induced O2·–. Our data obtained by knocking down GPx1, both in the human HEK293T cells and in rat neurons, together with the in vitro experiments, strongly suggest that endogenous γ-glutamylcysteine is a GPx1 cofactor for H2O2 detoxification. It cannot be ruled out that γ-glutamylcysteine could also act as a cofactor for other isoforms of the glutathione peroxidase family; however, GPx1 largely accounts for most mitochondrial H2O2 detoxification14, suggesting a major role for this isoform. Moreover, previous studies have shown that GPx1 can accept, albeit at a much lower efficiency, a range of thiol-derivatives besides GSH as the electron donor20. The essential cysteinyl-sulfhydryl and glutamyl-carboxylic groups for GPx1 active site interaction and catalysis14 are both preserved in γ-glutamylcysteine, indicating the structural feasibility for this function.

Due to its very low ability to synthesize and regenerate GSH, the brain is one of the most vulnerable tissues to excess ROS15,21. In Parkinson's disease, there is an ~60% reduction in GSH concentration in the substantia nigra of presymptomatic patients22, suggesting GSH deficiency as one of the earliest biochemical signs of this disorder. Moreover, signs of excess ROS are associated with the pathophysiology of other neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer's, or disorders affecting motor functional disturbances such as Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis or Huntington's disease23. At the light of our data, GPx1 is essential for γ-glutamylcysteine-mediated ROS detoxification and neuroprotection against different insults triggering neurodegeneration in primary neurons. Furthermore, we also show neuroprotection and motor improvement in an in vivo mouse model of neurodegeneration18. Thus, targeting γ-glutamylcysteine to neuronal mitochondria represents an improvement over the protection activity of neighbouring astrocytes24,25.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that γ-glutamylcysteine is a thiol-redox regulator that efficiently detoxifies mitochondrial ROS through GPx1. In the presence of γ-glutamylcysteine taking an antioxidant function, GSH stops from being oxidized; moreover, the ability of γ-glutamylcysteine to induce protein modification is well below that of GSH. Thus, when γ-glutamylcysteine takes the antioxidant functions, GSH utilization may be preserved for iron–sulfur cluster assembly and protein thiol-redox modifications, as recently reported9. How the antioxidant role of γ-glutamylcysteine is regulated under (patho) physiological conditions now needs to be deciphered. In this context, it should be noted that, besides GCL, alternative pathways can account for intracellular γ-glutamylcysteine2,3. For instance, γ-glutamyltransferase forms γ-glutamylcysteine at the extracellular side of the plasma membrane and then is taken up by the cells through the glutamyl-amino acid transporter2. It would be interesting to investigate if increased γ-glutamylcysteine could explain the drug resistance observed in tumours associated with γ-glutamyltransferase overexpression26. In addition, whether GSH deficiency is the prime mode of the pro-oxidant actions of the GCL/GSS/glutamyl-amino acid transporter inhibitor, L-buthionine sulfoximine4 needs to be revisited. Finally, our results, showing neuroprotection by mitochondrial-targeted γ-glutamylcysteine biosynthesis, supports the oxidative hypothesis of neurodegeneration27. Although classical antioxidant drugs failed in clinical trials against neurodegenerative disorders28, mitoGCL, by acting as a persistent antioxidant source for mitochondria, may represent a new gene therapy strategy to improve the transient efficacy of the formers.

Methods

Plasmids and lentivirus construction

To tag the catalytic subunit of human GCL with a mitochondrial-targeting epitope, the 5′-end of the full-length (2,023 bp) cDNA-encoding GCL (GenBank accession number NM_012815) was fused with a cDNA fragment encoding the first 32 amino acids of human ornithine transcarbamylase (GenBank accession number NM_000531). The forward and reverse oligonucleotides of this fragment were, respectively, 5′-GATCTATGCTGTTTAATCTGAGGATCCTGTTAAACAATGCAGCTTTTAGAAATGGTCACA ACTTCATGGTTCGAAATTTTCGGTGTGGACAACCACTACAAG-3′ and 5′-AATTCTTGTAGTGGTTGTCCACACCGAAAATTTCGAACCATGAAGTTGTGACCATTTCTA AAAGCTGCATTGTTTAACAGGATCCTCAGATTAAACAGCATA-3′ (BglII and EcoRI sites underlined; Thermo Scientific, Offenbach, Germany). The fused cDNA construct (mitoGCL) was inserted in pIRES2-EGFP (Invitrogen) vector and sequence-verified; mitoGCL was then subcloned into pcDNA3.1+ (Invitrogen) and pIRES2-DsRed2 (Clontech Laboratories Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA) with NheI/SmaI or NheI/XmaI restriction enzymes, respectively. For lentiviral particles production, the full-length cDNA-encoding mitoGCL, or its mutant inactive E103A form, was first digested with Eco47III/SmaI to generate blunt ends, and then subcloned in the PmeI site of pWPI lentiviral vector (Didier Trono laboratory, Lausanne, Switzerland). Recombinant lentiviruses were generated following a standard protocol29. Viral titters were determined by incubation of 3T3 cells with increasing dilutions of lentivirus in the presence of 8 μg ml−1 polybrene (Millipore), followed by green fluorescent protein (GFP) quantification by flow cytometry. Lentiviral particles were re-suspended to a final concentration of 1.7×106 plaque formation untis (p.f.u.) per μl. To direct GCL expression to the cytosol, we used non-tagged GCL. To knockdown GCL by small hairpin RNA (shRNA), a vector-based shRNA approach using the targeting sequence 5′-GAAGGAGGCTACTTCTATA-3′, as we described5, was used. The firefly luciferase-targeted oligonucleotide 5′-CTGACGCGGAATACTTCGA-3′ was used as control30. The forward and reverse 64-nt-long oligonucleotides were annealed and inserted into the BglII/HindIII sites of pSuper-neo/GFP vector (OligoEngine, Seattle, WA). These constructions concomitantly express 19-bp, 9-nucleotide stem-loop shRNAs with GFP, thus allowing the identification of transfected cells by fluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry.

Small interfering RNA construction

Using previously reported rational criteria31,32, we designed the following target sequences to get gene expression-specific knockdown by short interfering RNA (siRNA). For GSS: 5′-AGGAAATTGCTGTGGTTTA-3′ (nucleotides 856–874 for human NM_000178) and 5′-AGAGAAGGAAAGAAACATA-3′ (nucleotides 713–731 for rat NM_012962). For GSR: 5′-AGACGAATTCCAGAATACC-3′ (nucleotides 1211–1229 for human NM_000637) and 5′-GGACCTGAGTTTAAACAAA-3′ (nucleotides 1154–1172 for rat NM_053906). For glutathione peroxidase-1 (GPx1): 5′-CGCCAAGAACGAAGAGATT-3′ (nucleotides 338–356 for both human, NM_00581, and rat, NM_030826.3). SOD2 or MnSOD: 5′-GGGAGTTGCTGGAAGCCAT-3′ (nucleotides 381–399 for both human, NM_000636, and rat, NM_017051). In all cases, a siRNA against luciferase (5′-CTGACGCGGAATACTTCGATT-3′) was used as control. siRNAs were purchased from Dharmacon (Abgene, Thermo Fisher, Epsom, UK).

Site-directed mutagenesis

Mutant forms of mitoGCL refractory to the shRNA against GCL (mitoGCLmut) or catalytically inactive mitoGCL (mitoGCL (E103A)) were generated using the site-directed mutagenesis QuikChange XL kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA), followed by DpnI digestion. The forward and reverse oligonucleotides of the sequence 5′-GAAAGAAGCCACGTCAGTT-3′, carrying silent third-codon base point mutations (mutant nucleotides underlined) were used for mitoGCLmut. To generate mitoGCL (E103A), the forward and reverse oligonucleotides 5′-CAGAGTATGGGAGTTACATGATTGCAGGGACACCTGGCCAGCCGTACGGA-3′ (mutant nucleotides underlined) were used.

Cell cultures

Cortical neurons in primary culture were prepared from fetal Wistar rats (E16), seeded at 2.5×105 cells per cm2 in 6- or 12-well plates previously coated with poly-D-lysine (15 μg ml−1) in DMEM (Sigma, Madrid, Spain) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal calf serum (Roche Diagnostics, Heidelberg, Germany). Cells were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2-containing atmosphere. At 48 h after plating, the medium was replaced with DMEM supplemented with 5% horse serum (Sigma), 20 mM D-glucose and, on day 4, cytosine arabinoside (10 μM) to prevent non-neuronal proliferation33. Human embryonic kidney 293T (HEK293T) cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal calf serum. Cell transfections and treatments are specified in the Supplementary Methods. Cytosol was fractionated from mitochondria by differential centrifugation34.

Primary antibodies for western blotting

Immunoblotting was performed with rabbit polyclonal anti-GCL (1:1,000)5, rabbit polyclonal anti-GPX1 (1:1,000) (ab59546, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), rabbit polyclonal anti-GFP (1:1,000) (ab290, Abcam), mouse monoclonal anti-GSS (1:1,000) (Sc-166882, Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Heidelberg, Germany), mouse monoclonal anti-GSR (Sc-133159, Santa Cruz Biotechnologies), mouse monoclonal anti-SOD2 (1:2,000) (ab16,956, Abcam), rabbit polyclonal anti-VDAC (1:1,000) (Calbiochem, Darmstadt, Germany) or mouse monoclonal anti-GAPDH (1:40,000) (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; Ambion, Cambridge, UK) antibodies. VDAC and GAPDH were used as mitochondrial and cytosolic (or whole cell) loading controls, respectively.

Determination of ROS

Mitochondrial superoxide was detected using the fluorescent MitoSox probe (Invitrogen). Cells were incubated in Hank's buffer with 2 μM MitoSox-Red for 30 min at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere, washed with PBS and the fluorescence assessed by flow cytometry or fluorescence microscopy. We used the FL1, FL2 and FL3 channels of a FACScalibur flow cytometer (15 mW argon ion laser tuned at 488 nm; CellQuest software, Becton Dickinson Biosciences). Thresholds were adjusted by using non-stained and stained cells for MitoSOX fluorescence, and transfected and non-transfected cells for GFP fluorescence. For H2O2 assessment in isolated mitochondria, 50 μg protein-aliquots of freshly obtained mitochondria were incubated with 100 μM AmplexRed probe (Invitrogen) in mitochondrial respiration buffer (125 mM KCl, 2 mM KH2PO4, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mg ml−1 bovine serum albumin and 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4) containing horseradish peroxidase (0.5 U ml−1). Luminescence was recorded for 45 min at 1 min intervals using a Fluoroskan Ascent FL (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA) fluorimeter (excitation: 538 nm, emission: 604 nm), and the slopes were used for calculations. For H2O2 assessment in whole cell, 1.5×104 cells were incubated in 100 μM AmplexRed in Krebs-Ringer Phosphate buffer (145 mM NaCl, 5.7 mM Na2PO4, 4.86 mM KCl, 0.54 mM CaCl2, 1.22 mM MgSO4 and 5.5 mM glucose, pH 7.4), and the luminescence recorded as we did for mitochondria. Mitochondrial H2O2 was also detected by fluorescence microscopy in seeded, intact cells following the green fluorescence emitted by cells transfected with pHyPer-dMito plasmid vector (Evrogen, Moscow, Russia), which express a mitochondrial-tagged H2O2-sensitive fluorescent probe. In vitro H2O2 quantification was assessed as indicated in the Supplementary Methods.

Determination of γ-glutamylcysteine level and GCL activity

This was performed as described35. Cells were washed, colleted with 1 mM EDTA in PBS, pelleted (500g for 5 min) and re-suspended in isolation medium (320 mM sucrose, 10 mM Tris–HCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4). Samples (whole cells or isolated mitochondria) were freeze-thawed three times, and the lysates filtered through 10-kDa molecular mass cutoff devices (Amicon, Millipore) at 12,000g for 15 min at 4 °C. The retained protein fraction was immediately used for the determination of γ-glutamylcysteine concentration or assayed for GCL activity in 0.1 M Tris–HCl buffer containing 0.15 mM KCl, 20 mM MgCl2, 2 mM EDTA, 10 mM ATP, 10 mM L-cysteine, 40 mM L-glutamate and 220 μM acivicin, pH 8.2, at 37 °C for 15 min. The reaction was stopped by addition of ice-cold orthophosphoric acid (15 mM, final concentration), and the reaction product was immediately used for γ-glutamylcysteine determination. This was performed by high-pressure liquid chromatography using a LC-20A Shimadzu equipment (Shimadzu GmbH, Duisburg) with an interphase module (CBM-20A, Shimadzu GmbH) and electrochemical detection (ESA Biosciences, Inc., Chelmsford, MA), with the upstream electrode set at +100 mV (for compounds with low oxidation potential) and downstream electrode set between +100 and +650 mV (in +50 mV increments) for each injected standard to determine the optimum potential for detection. The samples were subjected to analysis with a Teknokroma MediterraneaSea18 ODS column (4.6×250 mm, 5-μm particle size), using 15 mM orthophosphoric acid as the mobile phase35 at a flow rate of 0.5 ml min−1. An external standard of 2.5–10 μM γ-glutamylcysteine (Bachem, Germany) was used for the calculations. In preliminary experiments, we tested that γ-glutamylcysteine synthesis was linear with the incubation time at least up to 20 min. Glutathione and other thiols, disulphides, and protein disulphides formed with low-molecular-weight thiols were assayed by ultra performance liquid chromatography and mass spectrometric detection as described in Supplementary Methods.

Protein determinations

Cells or tissues were lysed in 0.1 M NaOH and used for the determination of protein concentrations, either by the method of Lowry et al., as described36 or by the BCA protein assay kit (Pierce), following the manufacturer's instructions. In both cases, bovine serum albumin was used as standard.

Statistical analysis

All measurements in cell culture were carried out, at least, in triplicate, and the results are expressed as the mean±s.e.m. values from at least three different culture preparations. For the rotarod experiments, we used six to eight animals per condition. Statistical analysis of the results was performed by one-way analysis of variance, followed by the least significant difference multiple range test or by the Student's t-test for comparisons between two groups of values. In all cases, P<0.05 was considered significant.

Use of animals

All animals used in this wok were obtained from the Animal Experimentation Unit of the University of Salamanca, in accordance with Spanish legislation (RD 1201/2005) under licence from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation. Protocols were approved by the Bioethics Committee of the University of Salamanca.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Quintana-Cabrera, R. et al. γ-Glutamylcysteine detoxifies reactive oxygen species by acting as glutathione peroxidase-1 cofactor. Nat. Commun. 3:718 doi: 10.1038/ncomms1722 (2012).

References

Dickinson, B. C. & Chang, C. J. Chemistry and biology of reactive oxygen species in signaling or stress responses. Nat. Chem. Biol. 7, 504–511 (2011).

Meister, A. & Anderson, M. E. Glutathione. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 52, 711–760 (1983).

Veeravalli, K., Boyd, D., Iverson, B. L., Beckwith, J. & Georgiou, G. Laboratory evolution of glutathione biosynthesis reveals natural compensatory pathways. Nat. Chem. Biol. 7, 101–105 (2011).

Griffith, O. W., Bridges, R. J. & Meister, A. Transport of gamma-glutamyl amino acids: role of glutathione and gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 76, 6319–6322 (1979).

Diaz-Hernandez, J. I., Almeida, A., Delgado-Esteban, M., Fernandez, E. & Bolaños, J. P. Knockdown of glutamate-cysteine ligase by small hairpin RNA reveals that both catalytic and modulatory subunits are essential for the survival of primary neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 38992–39001 (2005).

Dalton, T. P., Dieter, M. Z., Yang, Y., Shertzer, H. G. & Nebert, D. W. Knockout of the mouse glutamate cysteine ligase catalytic subunit (Gclc) gene: embryonic lethal when homozygous, and proposed model for moderate glutathione deficiency when heterozygous. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 279, 324–329 (2000).

Shi, Z. Z. et al. Glutathione synthesis is essential for mouse development but not for cell growth in culture. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 97, 5101–5106 (2000).

Grant, C. M., MacIver, F. H. & Dawes, I. W. Glutathione synthetase is dispensable for growth under both normal and oxidative stress conditions in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae due to an accumulation of the dipeptide gamma-glutamylcysteine. Mol. Biol. Cell 8, 1699–1707 (1997).

Kumar, C. et al. Glutathione revisited: a vital function in iron metabolism and ancillary role in thiol-redox control. EMBO J. 30, 2044–2056 (2011).

Ristoff, E. et al. Glutathione synthetase deficiency: is gamma-glutamylcysteine accumulation a way to cope with oxidative stress in cells with insufficient levels of glutathione? J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 25, 577–584 (2002).

Griffith, O. W. & Meister, A. Origin and turnover of mitochondrial glutathione. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 82, 4668–4672 (1985).

Backos, D. S., Brocker, C. N. & Franklin, C. C. Manipulation of cellular GSH biosynthetic capacity via TAT-mediated protein transduction of wild-type or a dominant-negative mutant of glutamate cysteine ligase alters cell sensitivity to oxidant-induced cytotoxicity. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 243, 35–45 (2010).

Diaz-Hernandez, J. I., Moncada, S., Bolaños, J. P. & Almeida, A. Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 protects neurons against apoptosis induced by oxidative stress. Cell Death Differ. 14, 1211–1221 (2007).

Toppo, S., Flohe, L., Ursini, F., Vanin, S. & Maiorino, M. Catalytic mechanisms and specificities of glutathione peroxidases: variations of a basic scheme. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1790, 1486–1500 (2009).

Herrero-Mendez, A. et al. The bioenergetic and antioxidant status of neurons is controlled by continuous degradation of a key glycolytic enzyme by APC/C-Cdh1. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 747–752 (2009).

Almeida, A. & Bolaños, J. P. A transient inhibition of mitochondrial ATP synthesis by nitric oxide synthase activation triggered apoptosis in primary cortical neurons. J. Neurochem. 77, 676–690 (2001).

Murphy, M. P. How mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species. Biochem. J. 417, 1–13 (2009).

Beal, M. F. et al. Neurochemical and histologic characterization of striatal excitotoxic lesions produced by the mitochondrial toxin 3-nitropropionic acid. J. Neurosci. 13, 4181–4192 (1993).

Lok, J. et al. Gamma-glutamylcysteine ethyl ester protects cerebral endothelial cells during injury and decreases blood-brain barrier permeability after experimental brain trauma. J. Neurochem. 118, 248–255 (2011).

Flohe, L., Gunzler, W., Jung, G., Schaich, E. & Schneider, F. Glutathione peroxidase. II. Substrate specificity and inhibitory effects of substrate analogues. Hoppe Seylers Z Physiol Chem 352, 159–169 (1971).

Garcia-Nogales, P., Almeida, A. & Bolaños, J. P. Peroxynitrite protects neurons against nitric oxide-mediated apoptosis. A key role for glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase activity in neuroprotection. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 864–874 (2003).

Perry, T. L., Godin, D. V. & Hansen, S. Parkinson's disease: a disorder due to nigral glutathione deficiency? Neurosci. Lett. 33, 305–310 (1982).

Bolaños, J. P., Moro, M. A., Lizasoain, I. & Almeida, A. Mitochondria and reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in neurological disorders and stroke: therapeutic implications. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 61, 1299–1315 (2009).

Dringen, R. Metabolism and functions of glutathione in brain. Progr. Neurobiol. 62, 649–671 (2000).

Hardingham, G. E. & Lipton, S. A. Regulation of neuronal oxidative and nitrosative stress by endogenous protective pathways and disease processes. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 14, 1421–1424 (2011).

Corti, A., Franzini, M., Paolicchi, A. & Pompella, A. Gamma-glutamyltransferase of cancer cells at the crossroads of tumor progression, drug resistance and drug targeting. Anticancer Res. 30, 1169–1181 (2010).

Andersen, J. K. Oxidative stress in neurodegeneration: cause or consequence? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 5, S18–25 (2004).

Kamat, C. D. et al. Antioxidants in central nervous system diseases: preclinical promise and translational challenges. J. Alzheimers Dis. 15, 473–493 (2008).

Belzile, J. P. et al. HIV-1 Vpr-mediated G2 arrest involves the DDB1-CUL4AVPRBP E3 ubiquitin ligase. PLoS Pathog. 3, e85 (2007).

Ohtsuka, T. et al. ASC is a Bax adaptor and regulates the p53-Bax mitochondrial apoptosis pathway. Nat. Cell Biol. 6, 121–128 (2004).

Reynolds, A. et al. Rational siRNA design for RNA interference. Nat. Biotechnol. 22, 326–330 (2004).

Ui-Tei, K. et al. Guidelines for the selection of highly effective siRNA sequences for mammalian and chick RNA interference. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 936–948 (2004).

Almeida, A., Moncada, S. & Bolaños, J. P. Nitric oxide switches on glycolysis through the AMP protein kinase and 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase pathway. Nat. Cell Biol. 6, 45–51 (2004).

Almeida, A. & Medina, J. M. A rapid method for the isolation of metabolically active mitochondria from rat neurons and astrocytes in primary culture. Brain Res. Prot. 2, 209–214 (1998).

Gegg, M. E., Clark, J. B. & Heales, S. J. R. Determination of glutamate-cysteine ligase (γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase) activity by high-performance liquid chromatography and electrochemical detection. Anal. Biochem. 304, 26–32 (2002).

Lowry, O. H., Rosebrough, N. J., Lewis-Farr, A. & Randall, R. J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 193, 265–275 (1951).

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to Professor Rafael Radi (Montevideo, Uruguay) for his helpful discussions and revision of this manuscript. We also thank the technical assistance of Monica Resch, Monica Carabias and Virginia Fernandez. This work was funded by the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovacion (SAF2010-20008; Consolider-Ingenio CSD2007-00020; SAF2009-09500), Instituto de Salud Carlos III (PS09/0366), FEDER (European regional development fund) and the Junta de Castilla y Leon (GRX206; GRS244/A/08). R.Q.-C. is a recipient of a FIS Fellowship (FI07/00314).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.P.B. conceived the idea. J.P.B., R.Q.-C. and A.A. designed research. R.Q.-C., S.F.-F., V.B.-J., J.E., J.S. and A.A. performed research. J.P.B., R.Q.-C. and A.A. analysed the data. J.P.B. wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures S1-S2, Supplementary Tables S1-S3, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary References (PDF 441 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Quintana-Cabrera, R., Fernandez-Fernandez, S., Bobo-Jimenez, V. et al. γ-Glutamylcysteine detoxifies reactive oxygen species by acting as glutathione peroxidase-1 cofactor. Nat Commun 3, 718 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1722

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1722

This article is cited by

-

γ-Glutamylcysteine rescues mice from TNBS-driven inflammatory bowel disease through regulating macrophages polarization

Inflammation Research (2023)

-

Metabolomic analysis of rapeseed priming with H2O2 in response to germination under chilling stress

Plant Growth Regulation (2023)

-

Ameliorating Effect of Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells in a Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell Model of Dravet Syndrome

Molecular Neurobiology (2022)

-

Aberrant upregulation of the glycolytic enzyme PFKFB3 in CLN7 neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Intertwined ROS and Metabolic Signaling at the Neuron-Astrocyte Interface

Neurochemical Research (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.